Telemetric devices for vehicles, better known as black boxes, cracked the consumer scene 25 years ago with the premiere of OnStar. These days, you can get one for free from your insurance company if you want to try your luck at the discounts for safe driving game. But what if you wanted a black box just to mess around with that doesn’t share your driving data with the world? Just make one.

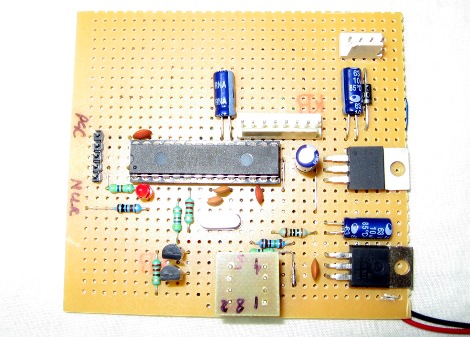

[TheForeignMan]’s DIY telematics box was designed to pull reports of the car’s RPM, speed, and throttle depression angle through the ODBII port. An ODBII-to-Bluetooth module sends the data to an Arduino Mega and logs it on an SD card along with latitude and longitude from a NEO-6M GPS module. Everything is powered by the car’s battery through a cigarette lighter-USB adapter.

He’s got everything tightly wrapped up inside a 3D printed box, which makes it pretty hard to retrieve the SD card. In the future, he’d like to send the data to a server instead to avoid accidentally dislodging a jumper wire.

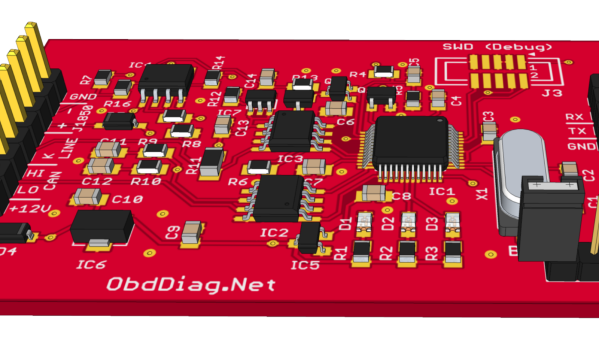

If this one isn’t DIY enough for you to emulate, start by building your own CAN bus reader.