Trawling classified ads or sites like Craigslist for interesting hardware is a pastime enjoyed by many a hacker. At a minimum, you can find good deals on used tools and equipment. But if you’re very lucky, you might just stumble upon something really special.

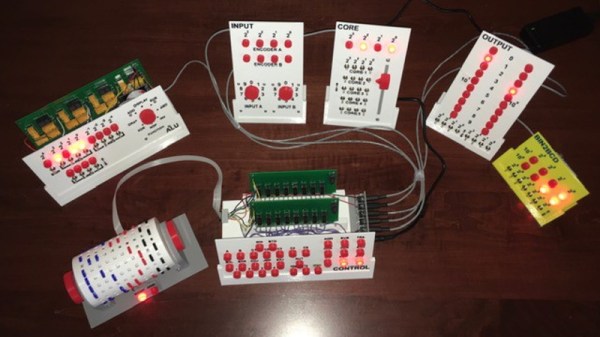

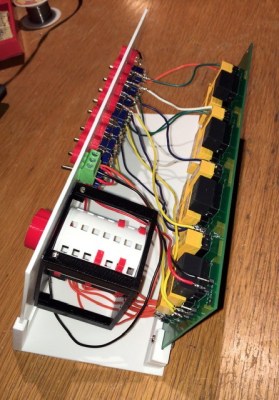

Which is exactly how [John] came into possession of the TRANSBINIAC. Included in a collection of gear that may have once belonged to a silent key, the device is a custom-built solid-state computer that appears to have been assembled in the early 1960s. Featuring a large see-through window not unlike what you might find on a modern gaming computer and a kickstand that tilts it back at a roughly 45° angle, it was obviously built to be shown off. Perhaps it was a teaching aid or even a science fair entry.

After some digging, it looks like the design of the TRANSBINIAC was based on plans published in the January 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated. Though there are some significant differences. This computer uses eight bistable flip-flip modules instead of the original six, deletes the multiplication circuit, and employs somewhat simplified wiring. Whoever built this machine clearly knew what they were doing, which for the time, is really saying something. This truly unique machine may well have been one of the first privately owned digital computers in the world.

Which is why we’re glad to see [John] trying to restore the device to its former glory. Naturally it’s a little tricky since the computer came with no documentation and its design doesn’t exactly match anything out there. But with the help of other Hackaday.io users, he’s hoping to get everything figured out. It sounds like the first step is to try and diagnose the 2N554 germanium transistor flip-flop modules, as they appear to be behaving erratically. If you have experience with this sort of hardware, feel free to chime in.

We’re supremely proud of the fact that so many of these early computer examples (and the people that are fascinated by them) have recently found their way to Hackaday.io. They’re literally the building blocks on which so much of our modern technology is based on, and the knowledge of how they were designed and operated deserves to live on for future generations to learn from. If it wasn’t for 1960s machines like the TRANSBINIAC or the so-called “Paperclip Computer”, Hackaday might not even exist. It seems like the least we can do is return the favor and make sure they aren’t forgotten.

[Thanks to Yann for the tip.]

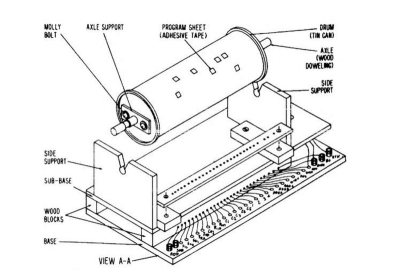

So what did you do if you were a kid saving money from a paper route in 1968 and you wanted to build a computer? Maybe you turned to

So what did you do if you were a kid saving money from a paper route in 1968 and you wanted to build a computer? Maybe you turned to