Forever.fm is [Peter]’s combination of SoundCloud and The Echo Nest that plays a continuous stream of beat-matched music. The result is a web radio station that just keeps playing.

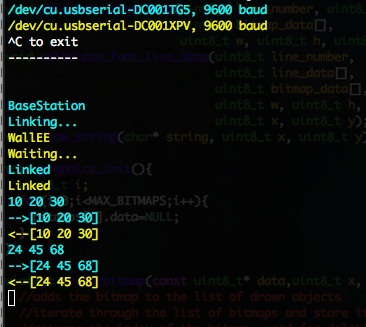

[Peter] provided a great write up on how he built the app. The server side is Python, using the Tornado web server and Tornadio2 + Socket.IO for handling live updates in the client. To deal with the challenge of streaming audio, he wrote a LAME interface for Python that handles encoding the raw, beat-matched audio into MP3 blocks. These blocks are queued up and sent out to the client by the web server.

Another challenge was choosing songs. Forever.fm takes the “hottest” songs from SoundCloud and creates a graph. Then it finds the shortest path to traverse the entire graph: a Travelling Salesman Problem. The solution used by Forever.fm finds an iterative approximation, then uses that to make a list of tracks. Of course, the resulting music is going to be whatever’s hot on SoundCloud. This may, or may not, match your personal tastes.

There’s a lot of neat stuff here, and [Peter] has open-sourced the code on his github if you’re interested in checking out the details.