The sky crane system used on the Perseverance and Curiosity Mars rovers is a challenging control system problem that piqued [Nicholas Rehm]’s curiosity. Constrained to Earth, he decided to investigate the problem using a drone and a rock.

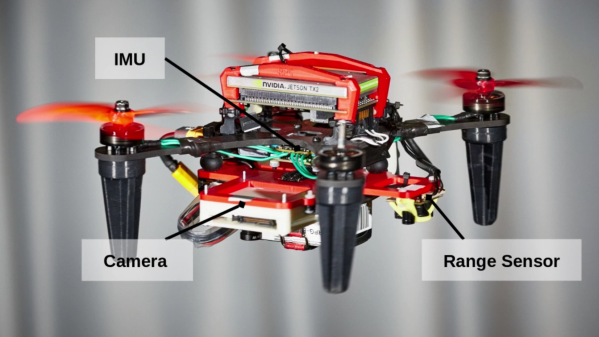

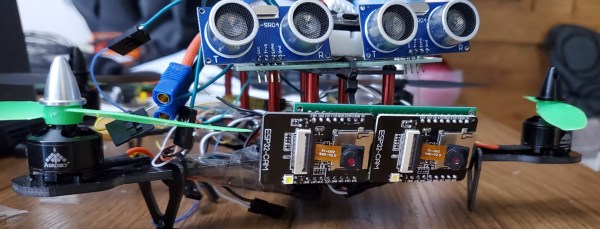

The setup and the tests are simple, but clearly illustrate the problem faced by NASA engineers. [Nicholas] attached a winch mechanism to the bottom of a racing-type quadcopter, and tied a mass to the end of the winch line. At first, he built a foam model of the rover, but it proved to be unstable in the wake of the quadcopter’s propellers, so he used a rock instead. The tests start with the quadcopter taking off with the rock completely retracted, which is then slowly lowered in flight until it reaches the end of the line and drops free. As soon as the rock was lowered, it started swinging like a pendulum, which only got worse as the line got longer. [Nicholas] attempted to reduce the oscillations with manual control inputs, but this only made it worse. The quadcopter is also running [Nicholas]’s own dRehmFlight flight controller that handles stabilization, but it does not account for the swinging mass.

[Nicholas] goes into detail on the dynamics of this system, which is basically a two-body pendulum. The challenges of accurately controlling a two-body pendulum are one of the main reasons the sky crane concept was shelved when first proposed in 1999. Any horizontal movement of either the drone or the rock exerts a force on the other body and will cause a pendulum motion to start, which the control system will not be able to recover from if it does not account for it. The real sky crane probably has some sort of angle sensing on the tether which can be used to compensate for any motion of the suspended rover. Continue reading “Demonstrating The Mars Rover Pendulum Problem With A Drone On Earth”