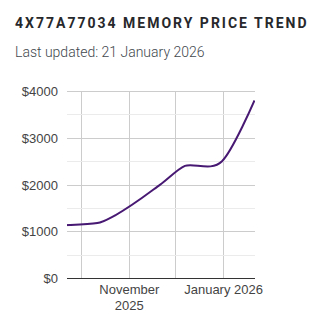

You’ve probably heard — we’re currently experiencing very high RAM prices due mostly to increased demand from AI data centers.

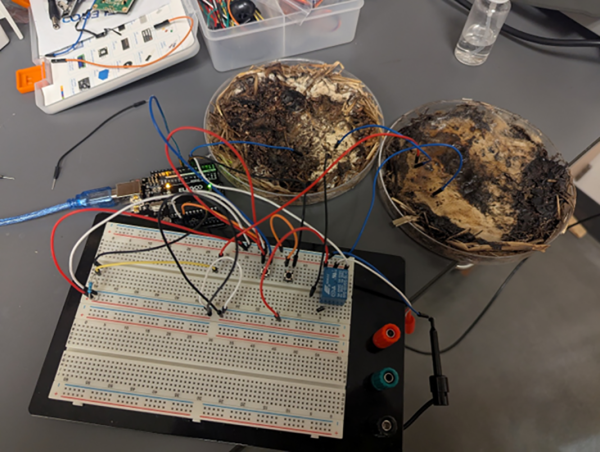

If you’ve been priced out of new RAM you are going to want to get as much value out of the RAM you already have as possible, and that’s where today’s hack comes in: if you’re on a Debian system read about ZRam for how to install and configure zram-tools to enable and manage the Linux kernel facilities that enable compressed RAM by integrating with the swap-enabled virtual memory system. We’ve seen it done with the Raspberry Pi, and the concept is the same.

Ubuntu users should check out systemd-zram-generator instead, and be aware that zram might already be installed and configured by default on your Ubuntu Desktop system.

If you’re interested in the history of in-kernel memory compression LWN.net has an old article covering the technology as it was gestating back in 2013: In-kernel Memory Compression. For those trying to get a grip on what has happened with RAM prices in recent history, a good place to track memory prices is memory.net and if you swing by you can see that a lot of RAM has gone up as much as four times in the last three or four months.

If you have any tips or hacks for memory compression on other platforms we would love to hear from you in the comments section!