Adafruit is working on a series of videos that’s basically Sesame Street for electronics. G is for Ground is out, where [Adabot] discovers pipes and lightning rods are connected to ground. Oh, the rhyming. Here’s the rest of the videos so far. We can’t wait for ‘Q is for Reactive Power’.

Think you’re good enough to build an airlock 70 cubic meters in volume that can cycle once every thirty seconds? How about building a 500 mile long steel tube with zero expansion joints across active fault lines? Can you stop a 3 ton vehicle traveling at 700 miles per hour in fifteen seconds? These are the near-impossible engineering challenges demanded of the hyperloop. The fact that no company will pay for this R&D should tell you something, but that doesn’t mean you still can’t contribute.

Calling everyone that isn’t from away. [Paul] lives near Augusta, Maine and can’t find a hackerspace. Augusta is the capital of the state, so there should be a hackerspace nearby. If you’re in the area, go leave a message on his profile.

Last week we found memristors you can buy. A few years ago, [Nyle] found them while hiking. They were crudded up shell casings, and experiments with sulfur and copper produced a memristor-like trace on a curve tracer.

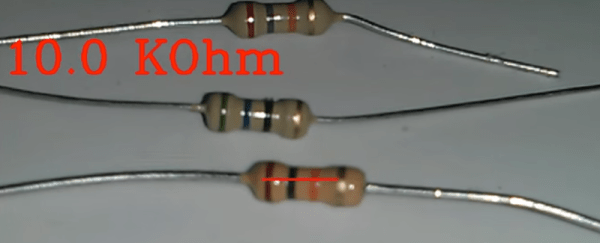

Need a way to organize resistors? Use plastic bags that are the same size as trading cards.

The Arduino is too easy. It must be packaged into a format that is impossible to breadboard. It should be shaped like a banana. Open source? Don’t need that. The pins are incorrectly labelled, and will be different between manufacturing runs.