We occasionally get stories on the tips line that just make us want to know more. This is especially true with tech stories covered by the mass media, which usually leave out the juicy tidbits that would just clutter up the story for the majority of non-technical readers. That leaves us to dig a little deeper for the satisfying details.

The latest one of these gems to hit the tips line is the tale of a regular broadband outage in a Welsh village. As in, really regular — at 7:00 AM every day, the internet customers of Aberhosan suffered a loss of their internet service. Customers of Openreach, the connectivity arm of the British telco BT, complained about the interruptions as customers do, and technicians responded to investigate the issue. Nobody was able to find the root cause, and despite replacing nearly all the cables in the system, the daily outages persisted for 18 months.

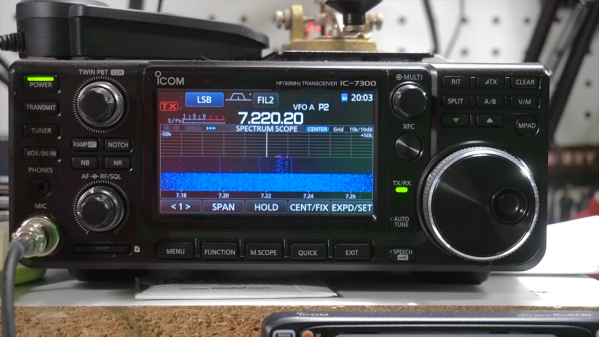

In the end, Openreach brought in a crack team from their Chief Engineer’s office to investigate. Working against COVID-19 restrictions, the team set up a spectrum analyzer in the early morning hours, to capture any evidence of whatever was causing the problem. At the appointed hour they saw a smear of radio frequency interference appear, a high-intensity pulse of noise at just the right frequency to interfere with the village’s asymmetric digital subscriber line (ADSL) broadband service.

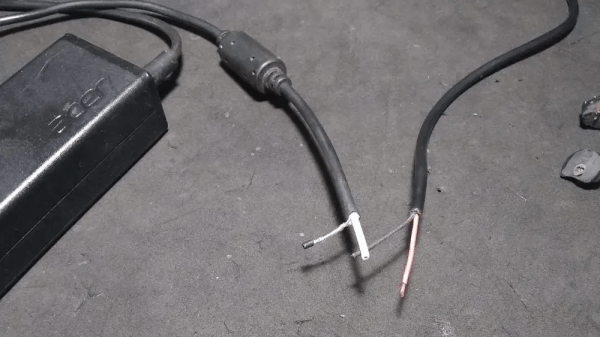

A little sleuthing led to the home of a villager and a second-hand TV, which was switched on every day at 7:00 AM. The TV was found to be emitting a strong RF impulse when it was powered up, strong enough to knock out the ADSL service to the entire village. Openreach categorized this as SHINE, or single high-level impulse noise. We’d never heard of this, but apparently it’s common enough that BT warns customers about it and provides helpful instructions for locating sources with an AM radio.

We’ll say one thing for the good people of Aberhosan: they must be patient in the extreme to put up with daily internet outages for 18 months. And it’s funny how there was no apparent notice paid by the offending television’s owner that his or her steady habit caused the outage. Perhaps they don’t have a broadband connection, and so wouldn’t have noticed the borking.

In any case, the owner was reportedly “mortified” by the news and hasn’t turned the TV on since learning of the issue. This generally seems to be the reaction when someone gets caught inadvertently messing up the spectrum — remember the Great Ohio Key Fob Mystery?

Thanks to [Kieran Donnelly] for spotting this for us.