Perhaps the most surprising thing about shadowgraphs is how simple they are: you simply take a point source of light, pass the light through a the volume of air to be imaged, and record the pattern projected on a screen; as light passes through the transition between areas with different refractive indices, it gets bent in a different direction, creating shadows on the viewing screen. [Degree of Freedom] started with these simple shadowgraphs, moved on to the more advanced schlieren photography, and eventually came up with a technique sensitive enough to register the body heat from his hand.

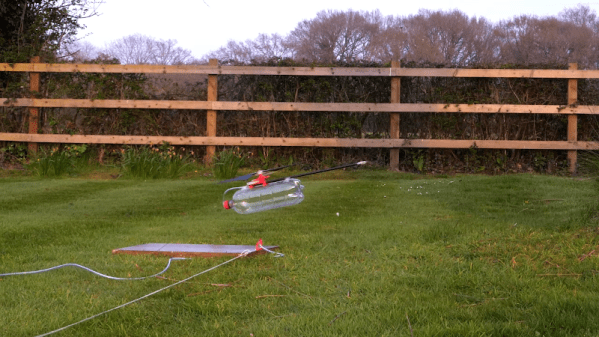

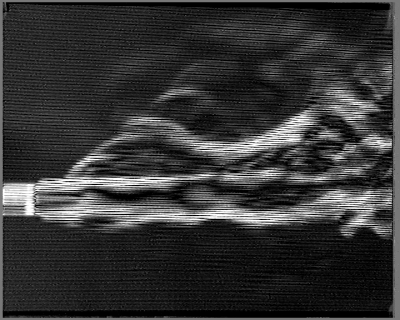

The most basic component in a shadowgraph is a point light source, such as the sun, which in experiments was enough to project the image of an escaping stream of butane onto a sheet of white paper. Better point sources make the imaging work over a wider range of distances from the source and projection screen, and a magnifying lens makes the image brighter and sharper, but smaller. To move from shadowgraphy to schlieren imaging, [Degree of Freedom] positioned a razor blade in the focal plane of the magnifying lens, so that it cut off light refracted by air disturbances, making their shadows darker. Interestingly, if the light source is small and point-like enough, adding the razor blade makes almost no difference in contrast.

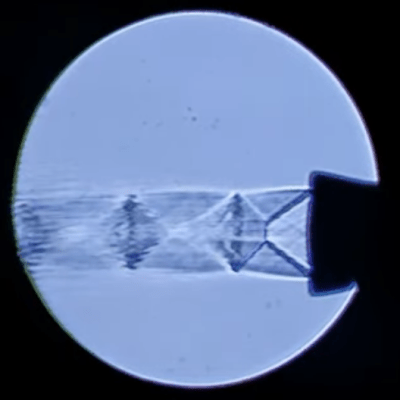

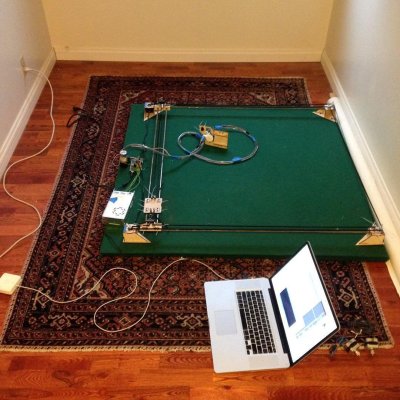

With this basic setup under his belt, [Degree of Freedom] moved on to more unique schlieren setups. One of these replaced the magnifying lens with a standard camera lens in which the aperture diaphragm replaced the razor blade, and another replaced the light source and razor with a high-contrast black-and-white pattern on a screen. The most sensitive technique was what he called double-pinhole schlieren photography, which used a pinhole for the light source and another pinhole in place of the razor blade. This could image the heated air rising from his hand, even at room temperature.

The high-contrast background imaging system is reminiscent of this technique, which uses a camera and a known background to compute schlieren images. If you’re interested in a more detailed look, we’ve covered schlieren photography in depth before.

Thanks to [kooshi] for the tip!