With ubiquitous desktop computing now several decades old, anyone creating an operating system distribution now faces a backwards compatibility problem. Each upgrade brings its own set of new features, but it must maintain compatibility with the features of the previous versions or risk alienating users. If you are a critic of Microsoft products for their bloat, this is one of the factors behind that particular issue.

As well as a problem of compatibility, this extra software overhead creates one of security. A piece of code descended from a DOS word processor of the 1980s for example was not originally created with any idea that it might one day be hiding in a library on a machine visible to the entire world by the Internet. Our subject today is a good example, just such a vulnerability hiding in an old piece of code whose purpose is to maintain an obscure piece of backward compatibility. [Chris Evans] has demonstrated a vulnerability in an Ubuntu version by playing an NES music file that contains exploit code emulated by the player on a virtual 6502 processor.

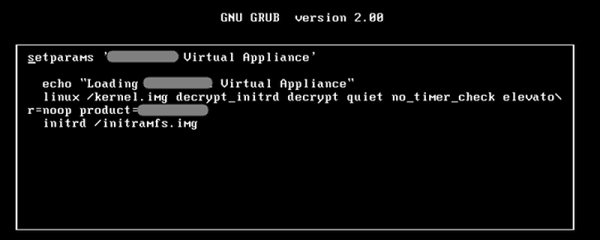

The NES Sound Format is a music file standard that packages Nintendo game music for playback. It contains a scripting language, and it is this that is used to trigger the vulnerability. When you open an NSF file on the affected Ubuntu system it finds its way via your music player and the gstreamer multimedia framework to libgstnsf.so, a gstreamer plugin for playing NSF files.

Rather unbelievably, his plugin works by emulating a real 6502 as found in a NES to derive the musical output, and it is somewhere here that the vulnerability exists. So not only do we have layer upon layer of backward compatibility to play an obscure music file format, there is also a software emulation of some 8-bit silicon from the 1970s. [Chris] comments “Is that cool or what?“, and while we agree that a 6502 emulator buried in a modern distro is cool, we can’t help thinking something’s been lost along the way.

A proof-of-concept is provided for Ubuntu 12.04. It’s an older version, but he points out that while he thinks the most recent releases should not contain exactly the same vulnerability, it certainly exists in more than one still-supported version. There’s also a worrying twist in that due to the vagaries of Ubuntu’s file manager it auto-opens when its folder is accessed from the GUI. The year 2000 called, they want their auto-opening Windows ME worms back.

Sadly we suspect the 6502 lurking in this music player can’t be put to more general-purpose use. If you manage it, please do share it with us! But if emulated 6502s are your thing, take a look at this 150MHz 6502 co-processor for an Acorn BBC Micro that someone made using a Raspberry Pi.

[via r/hacking]

6502 image, Dirk Oppelt, (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Wikimedia Commons.