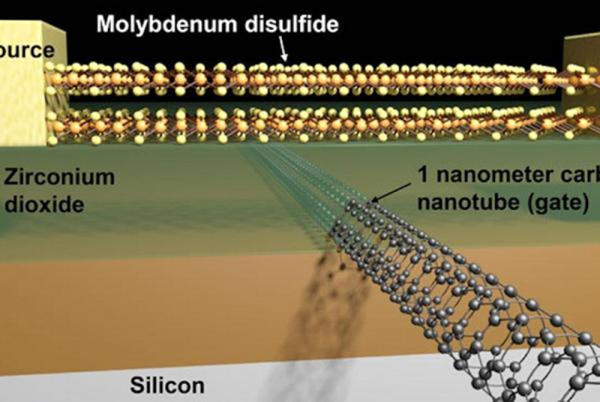

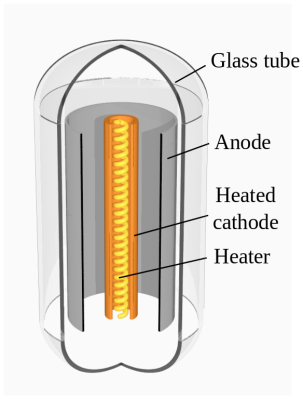

Since the 1940s when the first transistor was created, transistors have evolved from ornery blocks of germanium wrangled into basic amplifiers into thousands and thousands of different devices made of all kinds of material that make any number of electrical applications possible, cheap, and reliable. MOSFETs can come in at least four types: P- or N-channel, and enhancement or depletion mode. They also bear different power ratings. And some varieties are more loved than others; for instance, depletion-mode, N-channel power MOSFETs are comparatively scarce. [DeepSOIC] was trying to find one before he decided to make his own by hacking a more readily available enhancement-mode transistor.

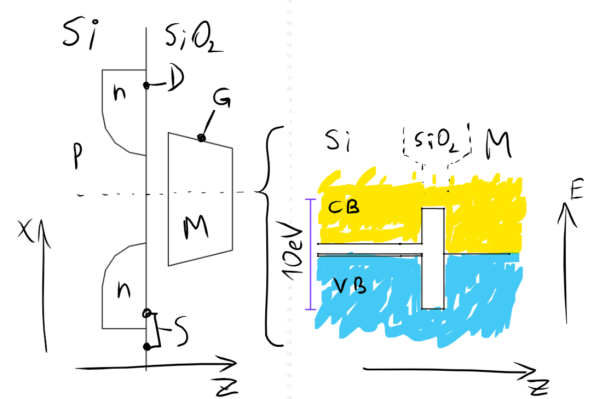

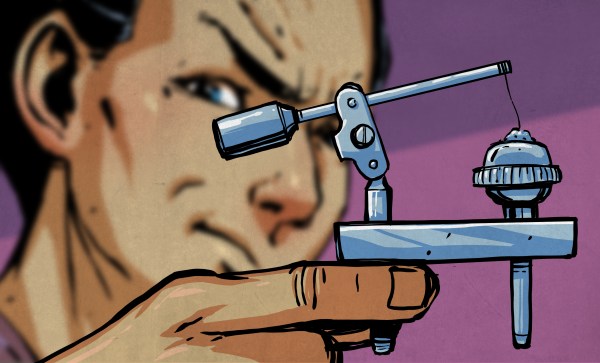

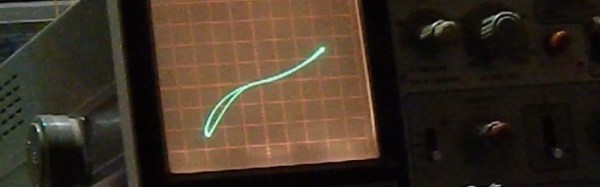

For those not intimately familiar with semiconductor physics, the difference between these two modes is essentially the difference between a relay that is normally closed and one that’s normally open. Enhancement-mode transistors are “normally off” and are easy to obtain and (for most of us) useful for almost all applications. On the other hand, if you need a “normally on” transistor, you will need to source a depletion mode transistor. [DeepSOIC] was able to create a depletion mode transistor by “torturing” the transistor to effectively retrain the semiconductor junctions in the device.

If you’re interested in semiconductors and how transistors work on an atomic level, [DeepSOIC]’s project will keep you on the edge of your seat. On the other hand, if you’re new to the field and looking to get a more basic understanding, look no further than these DIY diodes.