While early prototypes for SpaceX’s Starship have been exploding fairly regularly at the company’s Texas test facility, the overall program has been moving forward at a terrific pace. The towering spacecraft, which CEO Elon Musk believes will be the key to building a sustainable human colony on Mars, has gone from CGI rendering to flight hardware in just a few short years. That’s fast even by conventional rocket terms, but then, there’s little about Starship that anyone would dare call conventional.

Nearly every component of the deep space vehicle is either a technological leap forward or a deviation from the norm. Its revolutionary full-flow staged combustion engines, the first of their kind to ever fly, are so complex that the rest of the aerospace industry gave up trying to build them decades ago. To support rapid reusability, Starship’s sleek fuselage abandons finicky carbon fiber for much hardier (and heavier) stainless steel; a material that hasn’t been used to build a rocket since the dawn of the Space Age.

Then there’s the sheer size of it: when Starship is mounted atop its matching Super Heavy booster, it will be taller and heavier than both the iconic Saturn V and NASA’s upcoming Space Launch System. At liftoff the booster’s 31 Raptor engines will produce an incredible 16,000,000 pounds of thrust, unleashing a fearsome pressure wave on the ground that would literally be fatal for anyone who got too close.

Which leads to an interesting question: where could you safely launch (and land) such a massive rocket? Even under ideal circumstances you would need to keep people several kilometers away from the pad, but what if the worst should happen? It’s one thing if a single-engine prototype goes up in flames, but should a fully fueled Starship stack explode on the pad, the resulting fireball would have the equivalent energy of several kilotons of TNT.

Thanks to the stream of consciousness that Elon often unloads on Twitter, we might have our answer. While responding to a comment about past efforts to launch orbital rockets from the ocean, he casually mentioned that Starship would likely operate from floating spaceports once it started flying regularly:

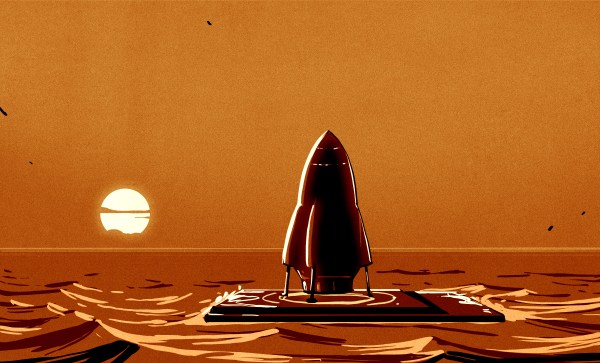

While history cautions us against looking too deeply into Elon’s social media comments, the potential advantages to launching Starship from the ocean are a bit too much to dismiss out of hand. Especially since it’s a proven technology: the Zenit rocket he references made more than 30 successful orbital launches from its unique floating pad.