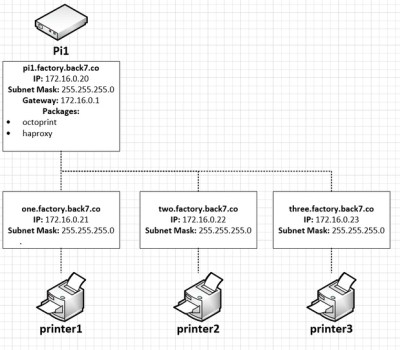

If you have a toddler and a mini-tramp you know the rallying cry of “Mama, Count!”. If you don’t don’t have either of these things, become the hero uncle or aunt by building one for your family members who have been social distancing with a three-year-old monster bundle of joy for the last five weeks. This trampoline bounce counter uses a Raspberry Pi and a distance sensor to stream the bounce count to a nice little web GUI.

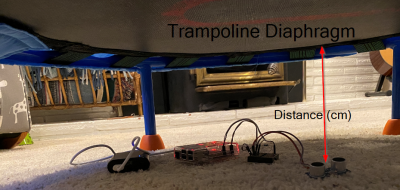

The hardware couldn’t be more simple, and there’s a good chance you already have everything on hand. The HC-SR04 ultrasonic distance sensor is a staple in beginner microcontroller kits. It simply lays on the floor pointed up at the bottom of the trampoline, connected to a Raspberry Pi via a resistor divider.

The hardware couldn’t be more simple, and there’s a good chance you already have everything on hand. The HC-SR04 ultrasonic distance sensor is a staple in beginner microcontroller kits. It simply lays on the floor pointed up at the bottom of the trampoline, connected to a Raspberry Pi via a resistor divider.

The software is where [Eric Escobar’s] project makes your life easy. He’s included a simple calibration routine that marks the low point of a bounce as you stand still on the tramp. There’s even a systemd service file included to ensure the software is always running, even after reboot. Cumulative bounce count can be seen on a webpage served from the Pi via an AJAX script.

Having a running count is a great first step, and surely a magical new feature of the trampoline that will be loved by the little ones. If that sense of wonder runs out, you could always gamify the system by adding in daily or hourly totals and a high-scores board.

It seems [Eric] is well practiced at automating his responsibilities away. We previously saw him use a Raspberry Pi to control the door of his chicken coop.

Continue reading “Trampoline Bounce Counter Has Raspberry Pi Automate Away Your Parental Duties”