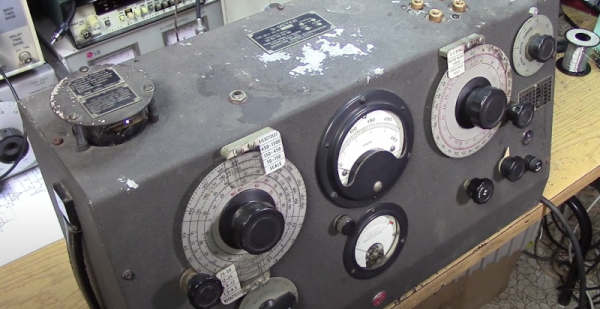

If you’ve ever dealt with RF circuits, you probably have run into Q — a dimensionless number that indicates the ratio of reactance to resistance. If you ever wanted to measure Q, you could do worse than pick up a vintage Boonton 160A Q meter. [Mikrowave1] did just that and shows us how it works in the video below.

Most often, the Q is of interest in an inductor. A perfect inductor would have zero resistance and be all reactance. If you could find one of those, it would have an infinite Q because you divide the reactance by the resistance. Of course, those inductors don’t exist. You can also apply Q to any circuit with reactance and the video talks about how to interpret Q for tuned circuits. You can also think of the Q number as the ratio of frequency to bandwidth or the dampening in an oscillator. A versatile measurement, indeed.

It sounds as though you could just measure the resistance of a coil and use that to compute Q. But you really need to know the total loss, and that’s not all due to resistance. A meter like the 160A uses a signal generator and measures the loss through the circuit.

The best part of the video is the teardown, though. This old tube gear is oddly beautiful in a strange sort of way. A real contrast to the miniaturized circuits of today. The Q meter is one of those nearly forgotten pieces of gear, like a grid dip oscillator. If you need to wind your own coils, by the way, you could do worse than see how [JohnAudioTech] does it.