“Round up the usual suspects…”

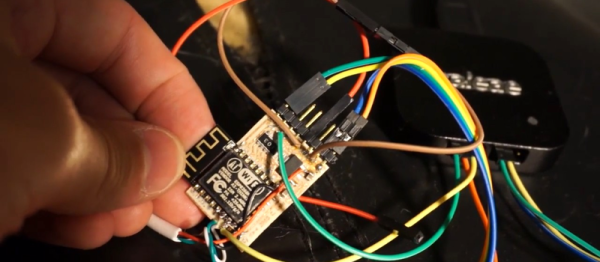

[CNLohr] just can’t get enough of the ESP8266 these days — now he’s working on getting a version of V-USB software low-speed USB device emulation working on the thing. (GitHub link here, video also embedded below.) That’s not likely to be an afternoon project, and we should warn you that it’s still a project in progress, but he’s made some in-progress material available, and if you’re interested either in USB or the way the mind of [CNLohr] works, it’s worth a watch.

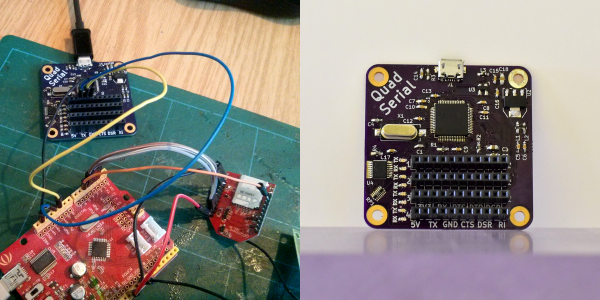

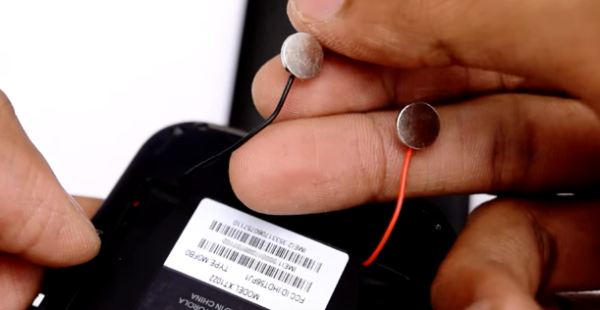

In this video, he leans heavily on the logic analyzer. He’s not a USB expert, and couldn’t find the right resources online to implement a USB driver, so he taught himself by looking at the signals coming across as he wiggled a mouse on his desk. Using the ever-popular Wireshark helped him out a lot with this task as well. Then it was time to dig into Xtensa assembly language, because timing was critical.

Speaking of timing, one of the first things that he did was write some profiling routines so that he could figure out how long everything was taking. And did we mention that [CNLohr] didn’t know Xtensa assembly? So he wrote routines in C, compiled them using the Xtensa GCC compiler, and backed out the assembly. The end result is a mix of the two: assembly when speed counts, and C when it’s more comfortable.