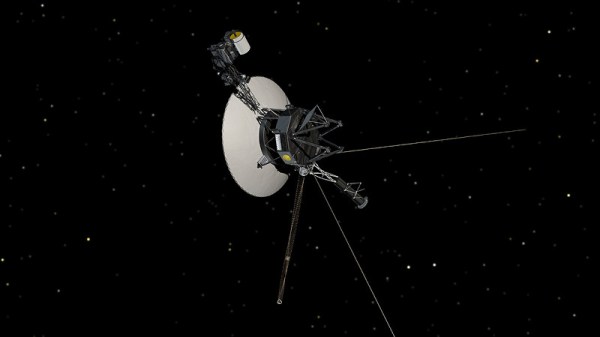

After more than forty-six years all of us are likely to feel the wear of time, and Voyager 1 is no different. Following months of harrowing troubleshooting as the far-flung spacecraft stopped returning sensible data, NASA engineers now feel confident that they have tracked down the cause for the problem: a single defective memory chip. Why this particular chip failed is unknown, but possibilities range from wear and tear to an energetic particle hitting it and disrupting its operation.

We’ve covered the Voyager 1 troubleshooting saga so far, with the initial garbled responses attributed to a range of systems, but narrowed down to the Flight Data Subsystem (FDS), which prepares data for transmission by the telemetry modulation unit (TMU). Based on a recent ‘poke’ command that returned a memory dump engineers concluded that the approximately 3% of corrupted data fit with this one memory chip, opening the possibility of a workaround.

Recently NASA engineers have also been working on patching up the firmware in both Voyager spacecraft, against the background of the dwindling energy produced by the radioisotope generators that have kept both spacecraft powered and warm, even in the cold, dark depths of Deep Space far beyond the light of our Sun.