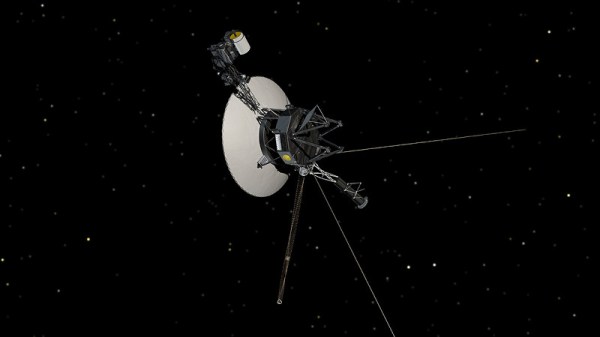

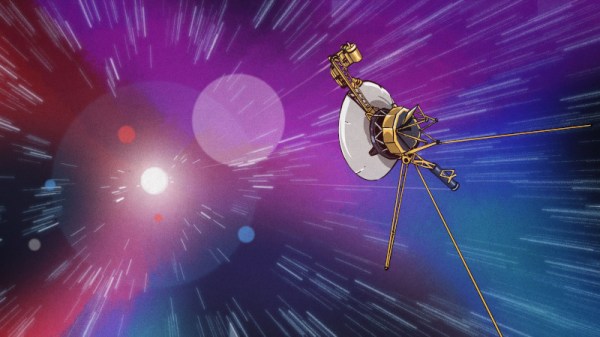

As humanity’s furthest reach into the Universe so far, the two Voyager spacecraft’s well-being is of utmost importance to many. Although we know that there will be an end to any science mission, the recent near-death experience by Voyager 1 was a shocking event for many. Now it seems that things may have more or less returned to normal, with all four remaining scientific instruments now back online and returning information.

Since the completion of Voyager 1’s primary mission over 43 years ago, five of its instruments (including the cameras) were disabled to cope with its diminishing power reserves, with two more instruments failing. This left the current magnetometer (MAG), charged particle (LECP) and cosmic ray (CRS) instruments, as well as the plasma wave subsystem (PWS). These are now all back in operation based on the returned science data after the Voyager team confirmed previously that they were receiving engineering data again.

With Voyager 1 now mostly back to normal, some housekeeping is necessary: resynchronizing the onboard time, as well as maintenance on the digital tape recorder. This will ensure that this venerable spacecraft will be all ready for its 47th anniversary this fall.

Thanks to [Mark Stevens] for the tip.

Underneath its icy surface, Europa appears to have a sea that contains twice as much water as we have here on Earth. Launching later this year and arriving in 2030, NASA’s Europa Clipper will provide us with our most up-close-and-personal look at the Jovian Moon yet. In conjunction with observations from the ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), scientists hope to gain enough new data to see if the conditions are right for life.

Underneath its icy surface, Europa appears to have a sea that contains twice as much water as we have here on Earth. Launching later this year and arriving in 2030, NASA’s Europa Clipper will provide us with our most up-close-and-personal look at the Jovian Moon yet. In conjunction with observations from the ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), scientists hope to gain enough new data to see if the conditions are right for life.