Over the past century or so we’ve come up with some clever ways of manipulating photons to do all kinds of interesting things. From lighting to televisions and computer screens to communication, including radio and fiber-optics, there’s a lot that can be done with these wave-particles and a lot of overlap in their uses as well. That’s why you can take something like a fairly standard Wi-Fi antenna meant for fairly short-range communication and use it for some other interesting tasks like downloading satellite data.

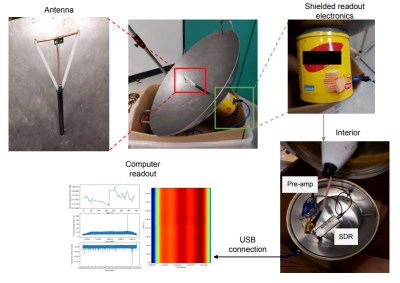

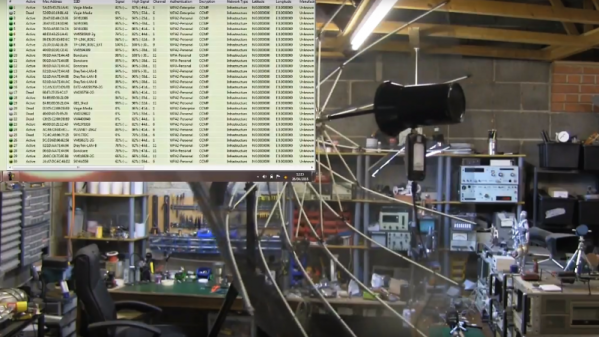

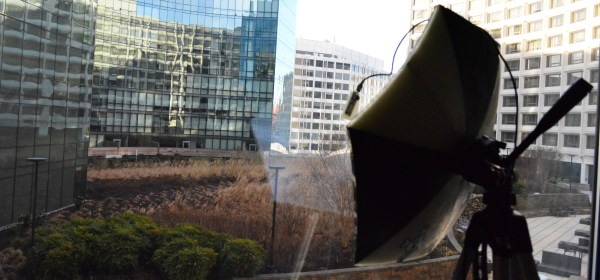

Weather satellites specifically use about the same frequency range as Wi-Fi, but need a bit of help to span the enormous distance. Normally Wi-Fi only has a range in the tens of meters, but attaching a parabolic dish to an antenna can increase the range by several orders of magnitude. The dish [dereksgc] found is meant for long-range Wi-Fi networking but got these parabolic reflectors specifically to track satellites and download the information they send back to earth. Weather satellites are generally the target here, and although the photons here are slightly less energy at 1.7 GHz, this is close enough to the 2.4 GHz antenna design for Wi-Fi to be perfectly workable and presumably will work even better in the S-band at around 2.2 GHz.

For this to work, [dereksgc] isn’t even using a dedicated tracking system to aim the dish at the satellites automatically; just holding it by hand is enough to get a readable signal from the satellite, especially if the satellite is in a geostationary orbit. You’ll likely have better results with something a little more precise and automated, but for a quick and easy solution a surprisingly small amount of gear is actually needed for satellite communication.

Continue reading “Downloading Satellite Imagery With A Wi-Fi Antenna”