We are used to stories about reverse engineering integrated circuits, in these pages. Some fascinating exposés of classic chips have been produced by people such as the ever-hard-working [Ken Shirriff].

You might think that this practice would be something new, confined only to those interested in the workings of now-obsolete silicon. But the secrets of these chips were closely guarded commercial intelligence back in the day, and there was a small industry of experts whose living came from unlocking them.

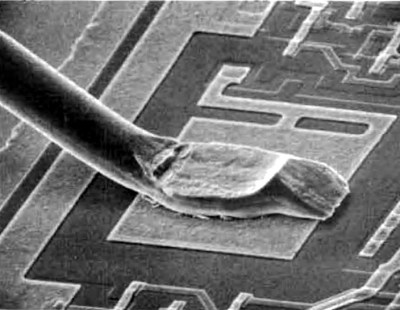

Integrated Circuit Engineering Corporation were a Scottsdale, Arizona based company who specialised in semiconductor industry data. They have long since been swallowed up in a series of corporate takeovers, but we have a fascinating window into their activities because their archive is preserved by the Smithsonian Institution. They reverse engineered integrated circuits to produce reports containing detailed information about their mechanical properties as well as their operation, and just such a report is our subject today. Their 1979 examination of the Zilog Z80 CTC (PDF) starts with an examination of the package, in this case the more expensive ceramic variant, then looks in detail at the internal construction of the die itself, and its bonding wires. We are then taken in its typewritten pages through an extensive analysis of the circuitry on the die, with gate-level circuits to explain the operation of each part.

The detail contained in this report is extraordinary, it is clear that a huge amount of work went into its production and it would have been of huge value to certain of Zilog’s customers and competitors. At the time this would have been extremely commercially sensitive information, even if it now seems like a historical curiosity.

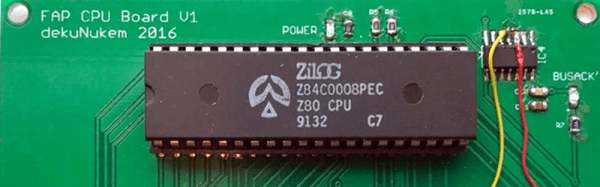

The Z80 CTC is a 4-channel counter/timer peripheral chip for the wildly succesful Z80 8-bit microprocessor, in a 28-pin dual-in-line package. We were surprised to find from a quick search that you can still buy this chip from some of the usual suppliers rather than the surplus houses, so it may even still be in production.

If IC reverse engineering takes your fancy, take a look at our archive of [Ken Shirriff] posts.

Thanks [fortytwo] for the tip.