So far, food for astronauts hasn’t exactly been haute cuisine. Freeze-dried cereal cubes, squeezable tubes filled with what amounts to baby food, and meals reconstituted with water from a fuel cell don’t seem like meals to write home about. And from the sound of research into turning asteroids into astronaut food, things aren’t going to get better with space food anytime soon. The work comes from Western University in Canada and proposes that carbonaceous asteroids like the recently explored Bennu be converted into edible biomass by bacteria. The exact bugs go unmentioned, but when fed simulated asteroid bits are said to produce a material similar in texture and appearance to a “caramel milkshake.” Having grown hundreds of liters of bacterial cultures in the lab, we agree that liquid cultures spun down in a centrifuge look tasty, but if the smell is any indication, the taste probably won’t live up to expectations. Still, when a 500-meter-wide chunk of asteroid can produce enough nutritionally complete food to sustain between 600 and 17,000 astronauts for a year without having to ship it up the gravity well, concessions will likely be made. We expect that this won’t apply to the nascent space tourism industry, which for the foreseeable future will probably build its customer base on deep-pocketed thrill-seekers, a group that’s not known for its ability to compromise on creature comforts.

A Homebrew Gas Chromatograph That Won’t Bust Your Budget

Chances are good that most of us will go through life without ever having to perform gas chromatography, and if we do have the occasion to do so, it’ll likely be on a professional basis using a somewhat expensive commercial instrument. That doesn’t mean you can’t roll your own gas chromatograph, though, and if you make a few compromises, it’s not even all that expensive.

At its heart, gas chromatography is pretty simple; it’s just selectively retarding the movement of a gas phase using a solid matrix and measuring the physical or chemical properties of the separated components of the gas as they pass through the system. That’s exactly what [Markus Bindhammer] has accomplished here, in about the simplest way possible. Gas chromatographs generally use a carrier gas such as helium to move the sample through the system. However, since that’s expensive stuff, [Markus] decided to use room air as the carrier.

The column itself is just a meter or so of silicone tubing packed with chromatography-grade silica gel, which is probably the most expensive thing on the BOM. It also includes an injection port homebrewed from brass compression fittings and some machined acrylic blocks. Those hold the detectors, an MQ-2 gas sensor module, and a thermal conductivity sensor fashioned from the filament of a grain-of-wheat incandescent lamp. To read the sensors and control the air pump, [Markus] employs an Arduino Uno, which unfortunately doesn’t have great resolution on its analog-to-digital converter. To fix that, he used the ubiquitous HX7111 load cell amplifier to read the output from the thermal conductivity sensor.

After purging the column and warming up the sensors, [Markus] injected a sample of lighter fuel and exported the data to Excel. The MQ-2 clearly shows two fractions coming off the column, which makes sense for the mix of propane and butane in the lighter fuel. You can also see two peaks in the thermal conductivity data from a different fuel containing only butane, corresponding to the two different isomers of the four-carbon alkane.

[Markus] has been on a bit of a tear lately; just last week, we featured his photochromic memristor and, before that, his all-in-one electrochemistry lab.

Continue reading “A Homebrew Gas Chromatograph That Won’t Bust Your Budget”

Retro Wi-Fi On A Dime: Amiga’s Slow Lane Connection

In a recent video, [Chris Edwards] delves into the past, showing how he turned a Commodore Amiga 3000T into a wireless-capable machine. But forget modern Wi-Fi dongles—this hack involves an old-school D-Link DWL-G810 wireless Ethernet bridge. You can see the Amiga in action in the video below.

[Chris] has a quirky approach to retrofitting. He connects an Ethernet adapter to his Amiga, bridges it to the D-Link, and sets up an open Wi-Fi network—complete with a retro 11 Mbps speed. Then again, the old wired connection was usually 10 Mbps in the old days.

To make it work, he even revived an old Apple AirPort Extreme as a supporting router since the old bridge didn’t support modern security protocols. Ultimately, the Amiga gets online wirelessly, albeit at a leisurely pace compared to today’s standards. He later demonstrates an upgraded bridge that lets him connect to his normal network.

We’ve used these wireless bridges to put oscilloscopes and similar things on wireless, but newer equipment usually requires less work even if it doesn’t already have wireless. We’ve also seen our share of strange wireless setups like this one. If you are going to put your Amgia on old-school networking, you might as well get Java running, too.

Continue reading “Retro Wi-Fi On A Dime: Amiga’s Slow Lane Connection”

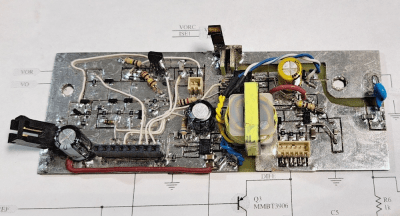

Building An Automotive Load Dump Tester

For those who have not dealt with the automotive side of electronics before, it comes as somewhat of a shock when you find out just how much extra you have to think about and how tough the testing and acceptance standards are. One particular test requirement is known as the “load dump” test. [Tim Williams] needed to build a device (first article of three) to apply such test conditions and wanted to do it as an exercise using scrap and spares. Following is a proper demonstration of follow-through from an analytical look at the testing specs to some interesting hand construction.

The load dump test simulates the effect of a spinning automotive alternator in a sudden no-load scenario, such as a loose battery terminal. The sudden reduction in load (since the battery no longer takes charging current) coupled with the inductance of the alternator windings causes a sudden huge voltage spike. The automotive standard ISO 7637-2:2011 dictates how this pulse should be designed and what load the testing device must drive.

The first article covers the required pulse shape and two possible driving techniques. It then dives deep into a case study of the Linear Tech DC1950A load dump tester, which is a tricky circuit to understand, so [Tim] breaks it down into a spice model based around a virtual transistor driving an RC network to emulate the pulse shape and power characteristics and help pin down the specs of the parts needed. The second article deals with analysing and designing a hysteric controller based around a simple current regulator, which controls the current through a power inductor. Roughly speaking, this circuit operates a bit like a buck converter with a catch diode circulating current in a tank LC circuit. A sense resistor in the output path is used to feedback a voltage, which is then used to control the driving pulses to the power MOSFET stage. [Tim] does a good job modeling and explaining some of the details that need to be considered with such a circuit.

Levitating Magnet In A Spherical Copper Cage

Lenz’s Law is one of those physics tricks that look like magic if you don’t understand what’s happening. [Seth Robinson] was inspired by the way eddy currents cause a cylindrical neodymium magnet to levitate inside a rotating copper tube, so he cast a spherical copper cage to levitate a magnetic sphere.

Metal casting is an art form that might seem simple at first, but is very easy to screw up. Fortunately [Seth] has significant experience in the field, especially lost-PLA metal casting. While the act of casting is quick, the vast majority of the work is in the preparation process. Video after the break.

[Seth] started by designing and 3D printing a truncated icosahedron (basically a low-poly sphere) in two interlocking halves and adding large sprues to each halve. Over a week, the PLA forms were repeatedly coated in layers of ceramic slurry and silica sand, creating a thick shell around them. The ceramic forms were then heated to melt and pour out the PLA and fired at 870°C/1600°F to achieve full hardness.

With the molds prepared, the molten copper is poured into them and allowed to cool. To avoid damaging the soft copper parts when breaking away the mold, [Seth] uses a sandblaster to cut it away sections. The quality of the cast parts is so good that 3D-printed layer lines are visible in the copper, but hours of cleanup and polishing are still required to turn them into shiny parts. Even without the physics trick, it’s a work of art. A 3d printed plug with a brass shaft was added on each side, allowing the assembly to spin on a 3D-printed stand.

[Seth] placed a 2″ N52 neodymium spherical magnet inside, and when spun at the right speed, the magnet levitated without touching the sides. Unfortunately, this effect doesn’t come across super clearly on video, but we have no doubt it would make for a fascinating display piece and conversation starter.

Using and abusing eddy currents makes for some very interesting projects, including hoverboards and magnetic torque transfer on a bicycle.

Continue reading “Levitating Magnet In A Spherical Copper Cage”

A VIC-20 With No VIC

[DrMattRegan] has started a new video series to show his latest recreation of a Commodore VIC-20. The core of the machine is [Ben Eater’s] breadboard 6502 design. To make it a VIC-20, though, you need a “VIC chip” which, of course, is no longer readily available. Many people, of course, use FPGAs or other programmable logic to fake VIC chips. But [Matt] will build his with discrete TTL logic. You can see the first installment of the series below.

All System Prompts For Anthropic’s Claude, Revealed

For as long as AI Large Language Models have been around (well, for as long as modern ones have been accessible online, anyway) people have tried to coax the models into revealing their system prompts. The system prompt is essentially the model’s fundamental directives on what it should do and how it should act. Such healthy curiosity is rarely welcomed, however, and creative efforts at making a model cough up its instructions is frequently met with a figurative glare and stern tapping of the Terms & Conditions sign.

Anthropic have bucked this trend by making system prompts public for the web and mobile interfaces of all three incarnations of Claude. The prompt for Claude Opus (their flagship model) is well over 1500 words long, with different sections specifically for handling text and images. The prompt does things like help ensure Claude communicates in a useful way, taking into account the current date and an awareness of its knowledge cut-off, or the date after which Claude has no knowledge of events. There’s some stylistic stuff in there as well, such as Claude being specifically told to avoid obsequious-sounding filler affirmations, like starting a response with any form of the word “Certainly.”

Continue reading “All System Prompts For Anthropic’s Claude, Revealed”