Adding LEDs to a project used to be enough to make it cool. But these days, you need arrays of addressable multi-color LEDs, and that typically means WS2812B or something similar. The problem is that while it was pretty easy to test garden-variety LEDs, these devices can be a bit harder to troubleshoot. [Gokux] has the answer, as you can see in the video below.

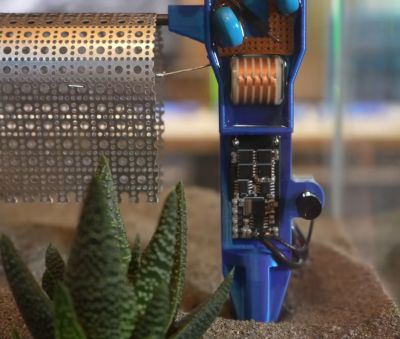

Testing these was especially important to [Gokux] because they usually swipe the modules from other modules or LED strips. The little fixture sends the correct pulses to push the LED through several colors when you hold it down to the pads.

However, what if the LED is blinking but not totally right? How can you tell? Easy, there’s a reference LED that changes colors in sync with the device under test. So, if the LEDs match, you have a winner. If not… well, it’s time to desolder another donor LED.

This is one of those projects that you probably should have thought of, but also probably didn’t. While the tester here uses a Xiao microcontroller, any processor that can drive the LEDs would be easy to use. We’d be tempted to breadboard the tester, but you’d need a way to make contact with the LED. Maybe some foil tape would do the trick. Or pogo pins.