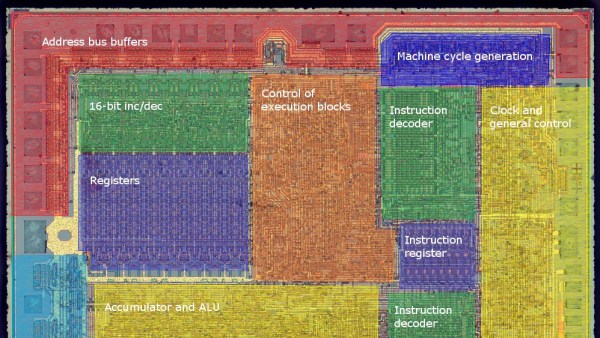

Early radio receivers worked on a principle called Tuned Radio frequency (TRF), patented in 1916. They weren’t very easy to use, requiring each stage to be tuned to the same frequency (until ganged capacitors made that a bit easy). The Superheterodyne design, devised in 1918, was superior, but more expensive at that time. Cost considerations led adoption of the Superhet design to lag behind TRF until almost 1930. Since then, until quite recently, the Superhet design has been at the heart of a majority of commercial radio receivers. Direct Conversion Receivers were devised around 1930, but required elaborate phase locked loops which restricted their use in commercial receivers. The point of all this background is that the Superhet design has served very well for more than 90 years, but will soon be rendered redundant once Software defined Radio (SDR) becomes ubiquitous. Which is why this study of the simple Superheterodyne shortwave receiver deserves closer study.

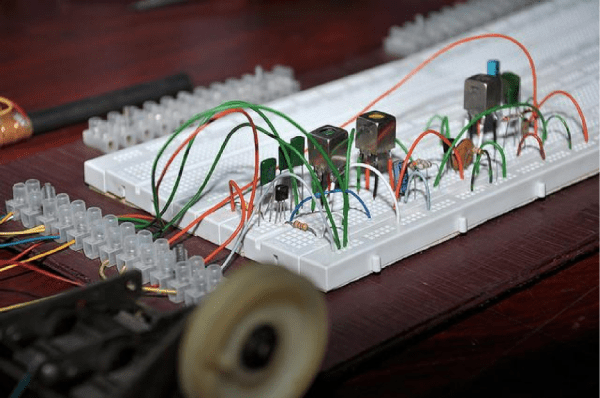

[Dilshan] built this two transistor and two IF transformer based superheterodyne radio designed to receive 13m to 41m bands. The whole build is assembled on a breadboard, making it easy to teach others to experiment. [Dilshan] offers very useful insights into antenna, rod coil and IF transformer parameters. To dive in to Radio architecture, check this post on Amateur Radio. And if you would like to get a closer look at Antique Radios, check this post on Restoring Antique Radios.