You need to use surface-mount technology (SMT) parts in your design. But you also need to prototype. How to fit those little buggers into your breadboard?

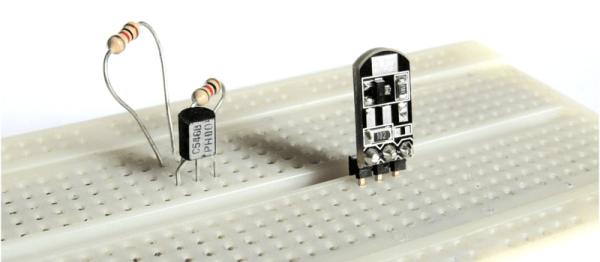

[Simon] came up with a general-purpose SMT-to-breadboard solution. Now, there are already myriad adapter boards for the many-pin devices: SSOP-to-DIP adapters and so on. But what do you do when you just need to work that tiny SOT223 voltage regulator into a breadboarded circuit?

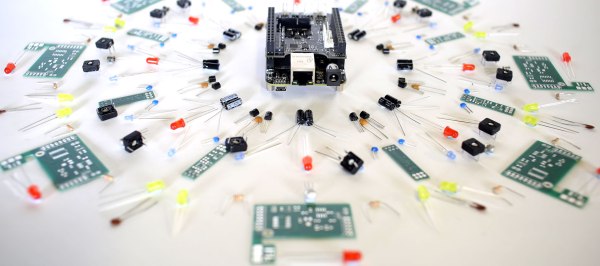

[Simon]’s solution fills that gap with one breadboardable design to handle all of your small-pin-count part needs. It accommodates SOT223, SOT323, and SOT23 three-pin parts like transistors or voltage regulators, and also has pads for all of the common two-terminal parts like resistors and capacitors from 0402 on up to 1206. You could build up a full voltage regulator circuit on one of these things. He’s even included some whitespace on the back for your notes.

SMT parts aren’t even the future any more. And with the right procedure, they’re not hard to hand-assemble. So the next time you have some extra space in a PCB order, toss in a couple of [Simon]’s breakouts and you’ll be ready for your next breadboarding session.