On Saturday, the Hackaday Community from across Ireland and other parts of Europe poured into the performance hall at Dublin’s Project Arts Centre for a massive collection of talks. From rediscovering century’s old technology, to cutting edge research projects, we heard talks from dozens of attendees on the technology that is interesting them most right now.

Choosing what to share about last weekend’s Uncon has been a particularly taxing process. So many and varied were the projects presented, and such was their high standard, that a writer faces a significant challenge to fit them into a single report. But we’ll give it a try. Read on for highlights of what was a weekend we will remember forever.

![[Rachel]'s about to lull us into a false sense of security with talk of fashion, then go for the eyeballs!](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/rachel-konichiwakitty.jpg?w=400)

From Wearables to Lab-Grown Eyeballs

Dublin by early April has lost some of winter’s chill, but the sun hadn’t regained control enough for the populace to have shed their coats and boots. It was in a slightly damp Temple Bar then that the Hackaday faithful convened at the Project Arts Centre, temporarily forsaking for us its role as one of Ireland’s most cutting-edge contemporary performing arts venues. We’d spent the previous day rounding up what seemed like Ireland’s entire stock of snack food to keep everyone happy, so it was into the upstairs performance hall for the day’s festivities. After putting in a talk topic and stopping by the swag table for goodies from our sponsor, DesignSpark, we all packed into the hall and began the Uncon.

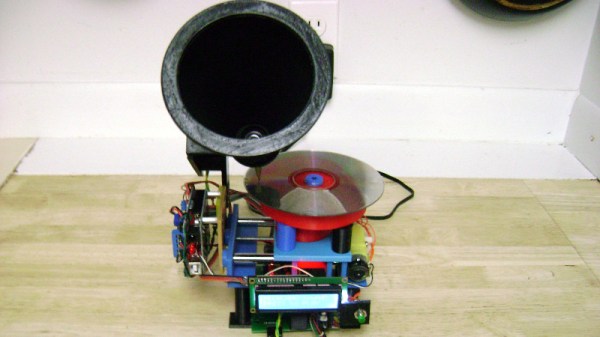

First to brave the floor was [Rachel “Konichiwakitty” Wong], who started by talking about her interest in and flair for wearable electronics applied to fashion. This is not however what she does for a living, and she soon switched from the kawaii to the everyday work of a stem cell research scientist. This section of her talk was entitled “The Future Of Medicine, stem cells, tissue engineering, off-the-shelf pick-n-mix organs”. Because of the work being done by people like her our hospitals may one day be able to prescribe custom 3D-printed organs for their patients, and her talk was a fascinating overview of that field for those of us who can not grow eyeball tissue on our benches.

There followed the exciting Unconference format, in which attendees were scheduled on-the-fly in four talk sessions throughout the day. Each deliver a seven-minute presentation and although it’s not compulsory to give an Unconference talk, there were definitely more than enough people wanting to give it a go. It’s impossible to mention them all in a single Hackaday piece, but here follows a selection of the many that caught our eye.

Continue reading “Dublin Unconference Roundup: The Topics That Are Hot Right Now”