With Russian military hardware quite literally raining down onto the ground in Ukraine, it’s little wonder that a sizeable part of PCBs and more from these end up being sold on EBay. This was thus where [msylvain] got a guidance board from a 300 mm Tornado-S 9M542 GLONASS-guided projectile from, for some exploration and reverse-engineering. The first interesting surprise was that the board was produced in February of 2023, with the Tornado-S system having begun production in 2016.

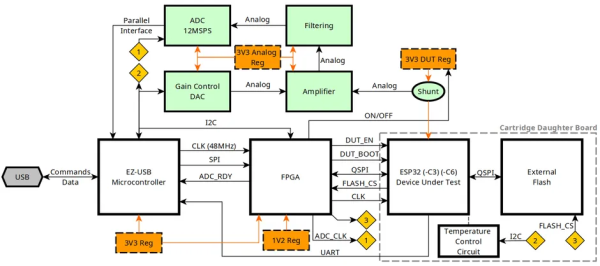

The 9M542 and similar rocket projectiles are designed to reach their designated area with as much precision as possible, which where the guidance system comes into play. Using both GLONASS and inertial navigation, the rocket’s stack of PCBs (pictured) are supposed to process the sensor information and direct the control system, which for the 9M542 consists out of four canards. The board that [msylvain] is looking at appears to be one of the primary PCBs, containing some DC-DC and logic components, as well as three beefy gate arrays (ULAs). While somewhat similar to FPGAs, these are far less configurable, which is why the logic ICs around it are needed to tie everything together. For this reason, gate array technology was phased out globally by the 1990s due to the competition of FPGAs, which makes this dual-sided PCB both very modern and instantly vintage.

This is where a distinct 1980s Soviet electronics vibe begins, as along the way of noting the function of each identified IC, it’s clear that these are produced by the same Soviet-era factories, just with date stamps ranging from 2018 to more recent and surface-mount DIP-sized packages rather than through-hole.

Continue reading “Reverse-Engineering A Russian Tornado-S Guidance Circuit Board”