Pip-Boy props are nothing new in the maker world, especially since the availability and prices of 3D printers have made the undertaking more straightforward. Something about bringing a piece of the Fallout universe into the real world is just incredibly appealing – so much so that Fallout 4 collector’s editions included a Pip-Boy phone case. However, because of practical limitations these props are usually just plastic shells that house a cell phone. [zapwizard] wasn’t satisfied with a purely aesthetic prop, so he has decided to design his own Pip-Boy 3000 Mk4 from scratch, while retaining as much of the functionality as possible.

For the few of you who are unfamiliar, the Pip-Boy is a wrist-mounted computer from the Fallout series of games. From a gameplay standpoint, it’s used to manage your character’s inventory, stats, quest data, and so on. Because of how often you interact with the Pip-Boy throughout the game, it has become very near and dear to the hearts of Fallout fans, which has driven it’s popularity for prop-making.

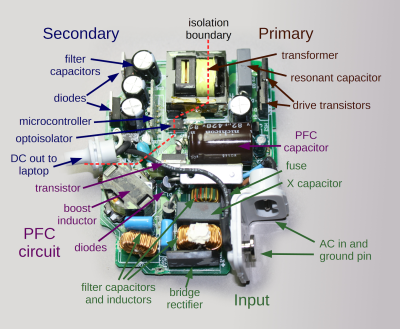

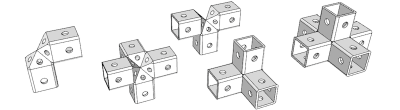

It’s no wonder, then, that we’ve featured a number of builds here on Hackaday in the past. All of these builds have been impressive, but [zapwizard] is taking it to a whole other level. As a product engineer, he certainly has the experience necessary to bring this to life, and he’s not skipping any details. He’s starting by modeling everything up in CAD, using Solid Edge. Every knob, button, dial, and latch has been reproduced in meticulous detail, and will be functional with completely custom electronics. [zipwizard] is still in the design phase, but he should be close to getting started on the actual build. He’s also considering offering a limited run of units for sale, so be sure to get in touch with him if that tickles your fancy!

[thanks Daniel Kennedy]