If you’ve been keeping your skills fresh with any console video games in the last 15 years (or you’ve acquired a smartphone), you’ll know that “rumble,” or “haptic” feedback plays a key role in augmenting our onscreen (or touch-screen typing) experience. Nevertheless, this sort of rumble feedback is surprisingly boolean, and hasn’t developed into a richer level of precision since it started to be introduced in gaming over 30 years ago. In response, [Martin] and his fellow design teammates at the University of Salzburg, Austria have introduced the TorqueScreen, a mobile haptic attachment that puts a twist on conventional force feedback.

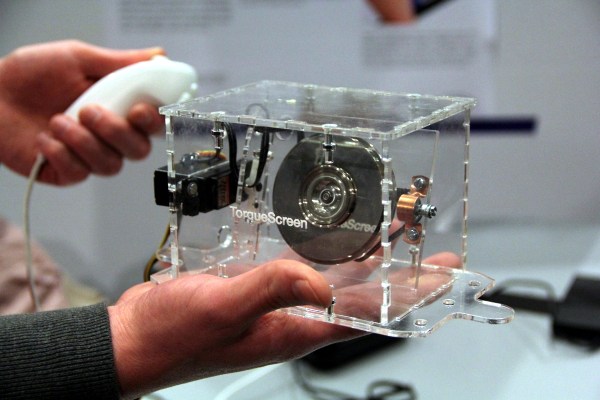

At its core the TorqueScreen is a gyroscope attached to a servo with the respective rotational axes in a perpendicular alignment. When the servo rotates the live gyroscope, the user can sense the tablet’s resistance to rotate about the servos axis.

The team’s conference demonstration model features a brushless motor plucked from an old hard drive controlled by an Arduino and driven manually by a Wii nunchuck. Currently only one rotational axis resists changes in rotation, but a gimbal may be the next step in this project.

We’ve certainly seen budget handheld haptic devices before, but this project allows for an entire spread of responses proportional to the speed at which the gyroscope is rotated about the servo axis.

Unless you’re reading this post on your already-torquescreen-enabled mobile device, it’s a bit difficult to get a feel for what kind of interactions you can produce with this setup. The video (after the break), though, can give you a pretty good idea of what kind of interactivity you’d expect with device clipped onto your tablet.

[via the Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction Conference]