You might be surprised to find out that [Akshat Joshi’s] Pong game that fits in a 512-byte boot sector isn’t the first of its kind. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t an accomplishment to shoehorn useful code in that little bitty space.

As you might expect, a game like this uses assembly language. It also can’t use any libraries or operating system functions because there aren’t any at that particular time of the computer startup sequence. Once you remember that the bootloader has to end with two magic bytes (0x55 0xAA), you know you have to get it all done in 510 bytes or less.

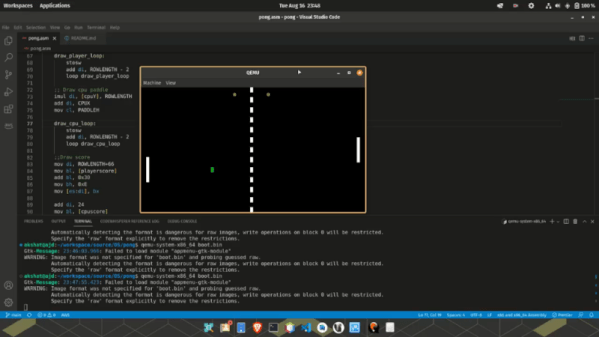

This version of Pong uses 80×25 text mode and writes straight into video memory. You can find the code in a single file on GitHub. In the old days, getting something like this working was painful because you had little choice but reboot your computer to test it and hope it went well. Now you can run it in a virtual machine like QEMU and even use that to debug problems in ways that would have made a developer from the 1990s offer up their life savings.

We’ve seen this before, but we still appreciate the challenge. We wonder if you could write Pong in BootBasic?