While coal was predominant in the past for energy generation, plants are shutting down worldwide to improve air quality and because they aren’t cost-competitive. It’s possible that idle infrastructure could be put to good use with fusion instead.

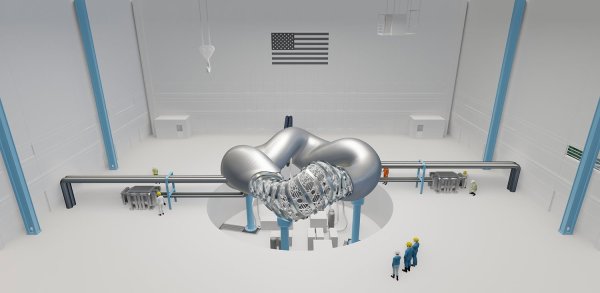

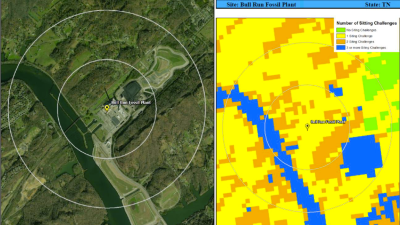

While we’ve yet to see a fusion reactor capable of generating electricity, Type One Energy, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and Oak Ridge National Lab have announced they’re evaluating the recently-closed Bull Run Fossil Plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee as a site for a nuclear fusion reactor. One of the main advantages for siting any new generation source on top of an old one is the ability to reuse the existing transmission infrastructure to get any generated power to the grid.

Don’t get too excited as it sounds like this is yet another prototype reactor that will be the proof-of-concept before construction of a reactor that can produce commercial power for the grid. While ambitious, the amount of investment by government entities like the Department of Energy and the state of Tennessee (>$55 million) seems to indicate they aren’t just blowing smoke.

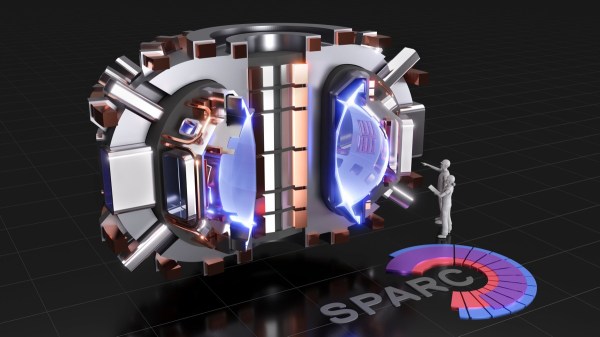

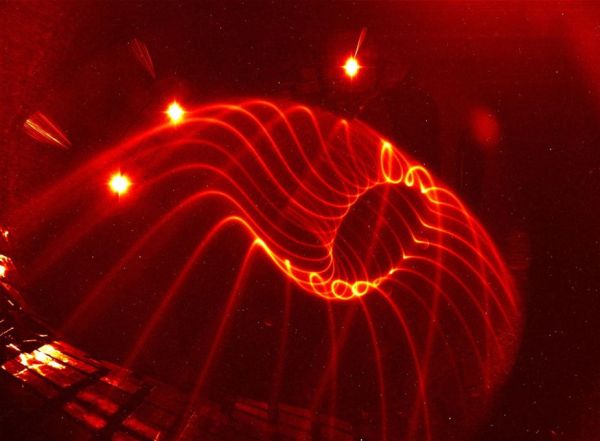

If any of this seems familiar, you might be thinking of the Department of Energy’s report on placing advanced fission reactors on old coal sites. A little fuzzy on the difference between a stellarator and a tokamak? Checkout this explainer on some of the different ways to (non-explosively) do fusion on Earth.