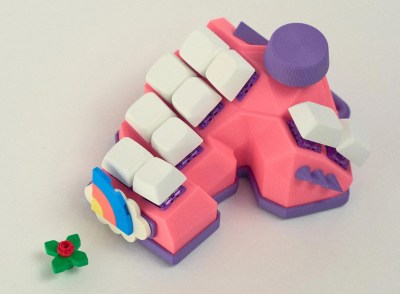

Magnetic materials are typically divided into ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic types, depending on their magnetic moments (electron spins), resulting in either macroscopic (net) magnetism or not. Altermagnetism is however a recently experimentally confirmed third type that as the name suggests alternates effectively between these two states, demonstrating a splitting of the spin energy levels (spin-split band structure). Like antiferromagnets, altermagnets possess a net zero magnetic state due to alternating electron spin, but they differ in that the electronic band structure are not Kramers degenerate, which is the feature that can be tested to confirm altermagnetism. This is the crux of the February 2024 research paper in Nature by [J. Krempaský] and colleagues.

Specifically they were looking for the antiferromagnetic-like vanishing magnetization and ferromagnetic-like strong lifted Kramers spin degeneracy (LKSD) in manganese telluride (MnTe) samples, using photoemission spectroscopy in the UV and soft X-ray spectra. A similar confirmation in RuO2 samples was published in Science Advances by [Olena Fedchenko] and colleagues.

What this discovery and confirmation of altermagnetism means has been covered previously in a range of papers ever since altermagnetism was first proposed in 2019 by [Tomas Jungwirth] et al.. A 2022 paper published in Physical Review X by [Libor Šmejkal] and colleagues details a range of potential applications (section IV), which includes spintronics. Specific applications here include things like memory storage (e.g. GMR), where both ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetics have limitations that altermagnetism could overcome.

Naturally, as a fairly new discovery there is a lot of fundamental research and development left to be done, but there is a good chance that within the near future we will see altermagnetism begin to make a difference in daily life, simply due to how much of a fundamental shift this entails within our fundamental understanding of magnetics.

Heading image: Illustrative models of collinear ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism, and altermagnetism in crystal-structure real space and nonrelativistic electronic-structure momentum space. (Credit: Libor Šmejkal et al., Phys. Rev. X, 2022)