Neutrinos are some of the strangest particles we have encountered so far. About 100 billion of them are going through every square centimeter on Earth per second but their interaction rate is so low that they can easily zip through the entire planet. This is how they earned the popular name ‘ghost particle’. Neutrinos are part of many unsolved questions in physics. We still do not know their mass and they might even be there own anti-particles while their siblings could make up the dark matter in our Universe. In addition, they are valuable messengers from the most extreme astrophysical phenomena like supernovae, and supermassive black holes.

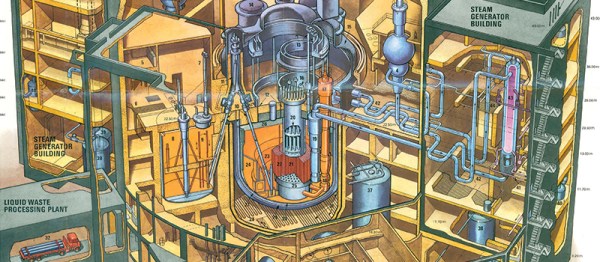

The neutrinos on earth have different origins: there are solar neutrinos produced in the fusion processes of our sun, atmospheric neutrinos produced by cosmic rays hitting our atmosphere, manmade reactor neutrinos created in the radioactive decays of nuclear reactors, geoneutrinos which stem from similar processes naturally occurring inside the earth, and astrophysical neutrinos produced outside of our solar system during supernovae and other extreme processes most of which are still unknown. Continue reading “Hunting Neutrinos In The Antarctic”