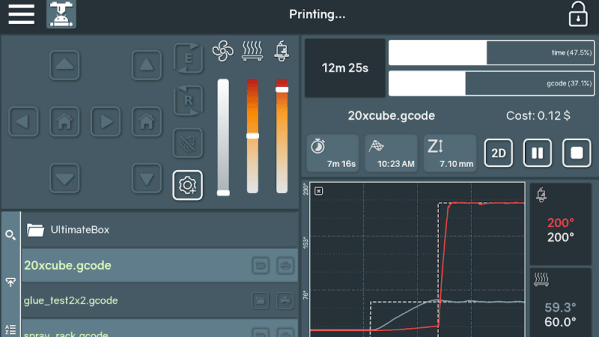

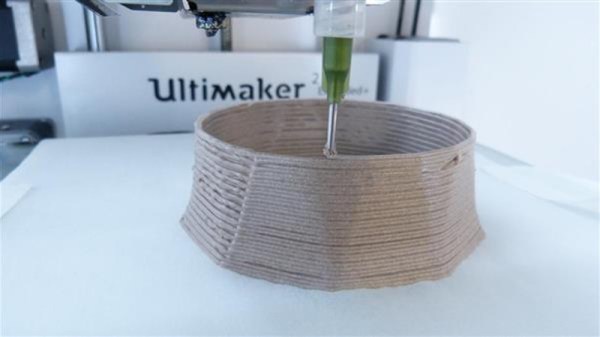

Not too long ago I took the plunge into the world of OctoPrint by shoehorning a Raspberry Pi Zero into a PrintrBot Play, and I have to say, the results were quite impressive. OctoPrint allows you to run your 3D printer untethered from your computer, but without all the downsides of printing off of an SD card. Generally running off of a Raspberry Pi, OctoPrint serves up a very capable web interface that gives you full control over slicing and printing from essentially any device with a modern browser.

That’s all well and good if you’ve got your laptop with you, or you’re sitting at your desktop. But what if you’re out of the house? Or maybe out in the garage where you don’t have a computer setup? OctoPrint is still happily serving up status information and a control interface, you just don’t have a computer to access it. Luckily, there are options for just that scenario.

In this post we’re going to take a look at a couple of options for controlling and monitoring OctoPrint from your mobile device, which can help truly realize its potential. Personally I have an incredible amount of anxiety when leaving a 3D printer running a long job, and in the past I’ve found myself checking every 10 minutes or so to see if it was done. Now that I can just glance at my phone and see an ETA along with status information about the machine, it’s given me the confidence to run increasingly longer and complex prints. Continue reading “Controlling OctoPrint On The Go”