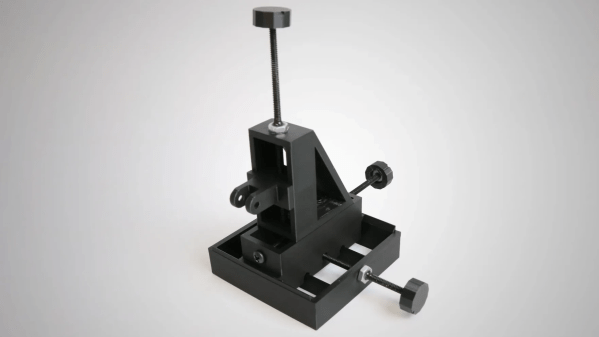

There are times in every 3D print enthusiast’s life when it would be convenient to join two pieces of filament. The problem with simply melting them together is that the resulting join has a blob of plastic surrounding it which has difficulty making it through the printer’s internals. [Pete Prodoehl] has a solution, in the form of a well-executed splicing jig that’s sure to leave a join which will glide through your printer.

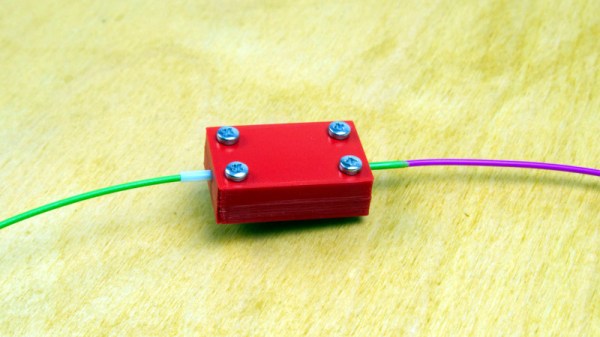

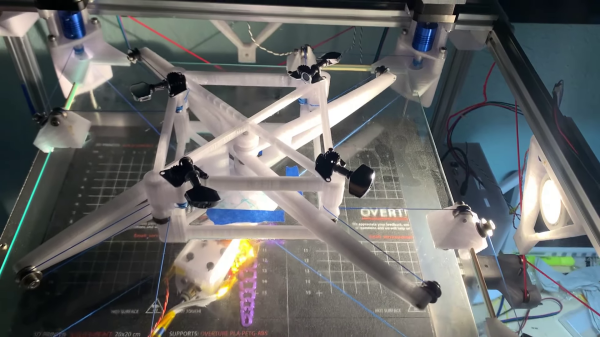

The trick lies in performing the join in a space only marginally wider than the filament width, in the case of 1.75 mm filament a short piece of 1.775 mm PTFE tube encased in a 3D printed clamp. A 90-degree cut piece of filament is fed through the tube and heated with a candle, then withdrawn into the tube where a 45-degree cut piece is pushed in to fuse with it. The result is a seamless and bulge-less join, that can pass through an extruder without issue and print continuous pieces from different filaments.

It’s a very effective technique, but it’s not the only one we’ve seen over the years. This one by comparison heats the filament in a hair straightener, and relies on gently pulling the join apart as it solidifies in order to reduce the bulge.