The BBC, as the British national broadcaster for so many decades, now finds itself also performing the function of keeper of a significant part of the collective national memory. Thus they have an unrivaled resource of quality film and audio recordings on hand for when they look back on the anniversary of a particular story, and the retrospectives they create from them can make for a particularly fascinating read.

This week has seen the fiftieth anniversary of a very unusual event, the day six flying saucers were found to have crash-landed in a straight line across the width of Southern England. It was as though a formation of invaders had entered the atmosphere in a manoeuvre gone wrong, and maintained their relative positions as they hurtled towards the unsuspecting countryside.

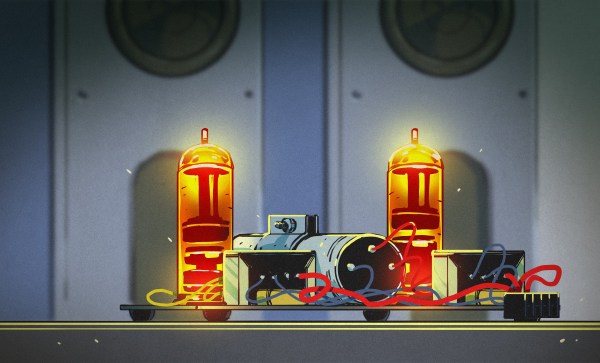

Except of course, there were no aliens, and there were no flying saucers. Instead there was a particularly resourceful group of apprentices from the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, and the saucers were beautifully made fibreglass and metal creations. They contained electronic sound generators to give an alien-sounding beeping noise, and a fermenting mixture of flour and water for an alien-looking ectoplasmic goo should anybody decide to drill into them. The police were called and the RAF were scrambled, and a media frenzy occurred before finally the jolly hoaxters were unmasked. In those simpler times everyone had a good laugh and got on with their lives, while without a doubt now there would have been a full-blown terrorism scare and a biohazard alert over all that flour paste.

A Hackaday writer never admits her age, but this is a story that happened well before the arrival of this particular scribe. We salute and envy these 1960s pranksters, and hope that they went on to do great things. If you are a British resident you can see an accompanying TV report on their southern regional news programme, Inside Out, on BBC One South East and South today at 19:30 BST, or via BBC iPlayer should you miss it.

Flying saucer confectionery image: jo-h [CC BY 2.0].