Winter is coming, along with mittens, cold hands, snow, and jackets. Now that we’re all carrying around lithium batteries in our pocket, wouldn’t it be a great idea to build an electronic hand warmer? That’s what [GreatScott!] thought. To build his electronic hand warmer, he turned to the most effective and efficient way to turn electricity into heat: a ten-year-old AMD CPU.

Building an electronic hand warmer is exceptionally simple. All you need is a resistive heating element (like a resistor), a means to limit current (like a resistor), and a power supply (like a USB power bank). Connect these things together and you have a hand warmer that is either zero percent or one hundred percent efficient. We haven’t figured that last part out yet.

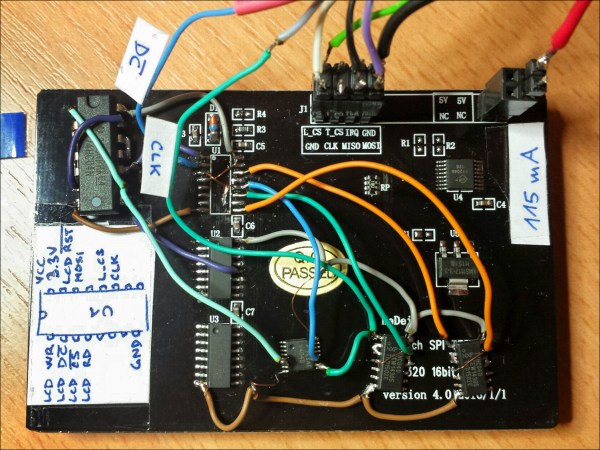

Because more power and more retro is more betterer, [GreatScott] pulled an AMD Sempron out of an old computer. Finding and reading data sheets is for wimps, apparently, so [GreatScott] just poked some pins with a variable power supply until the CPU was drawing about 500mA at 5V.

The video continues with some Arduino-based temperature measurement, finding some new pins to plug the power leads into, and securing all the wires on this heating element with hot glue. For anyone in the comments ready to say, ‘not a hack’, we assure you, this qualifies.

With the naive method of building a CPU hand warmer out of the way, here’s the pros and cons of this project, and how it can be made better. First off, using an old AMD processor was a great idea. These things are firestarters, and even though this processor preceded the 100+ W TDP AMD CPUs, it should work well enough.

That said, this is not how you waste power in a CPU. Ideally, the processor should do some work, with more active gates resulting in higher power consumption. If this were an exceptionally old processor, a good, simple option would be freerunning the chip, or having the CPU count up through its address space. This can be done by tying address lines low or high, depending on the chip. That’ll waste a significant amount of power. Randomly poking pins hoping for the right power consumption is not the way to get the most heat out of this CPU.

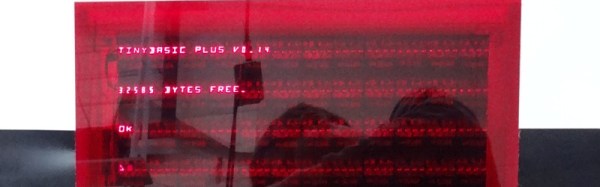

Of course, the above paragraph is just theory. The eating is in the pudding, or some other disfigured colloquialism, so here’s a quad-core 386 coffee warmer. This project from [magnustron] uses four 80386 CPUs powered via USB to make a nice desktop hotplate for your cuppa. Of course being powered by USB means there’s only 500mA to go around, and the ΔT is comparable to [GreatScott]’s AMD and hot glue hand warmer. Thus we get to the crux of the issue: 5V and 500mA isn’t very hot. Until cheap USB-C power banks, with ten or twelve Watts flood in from China, the idea of a USB powered heater is a fool’s errand. It does make for some great AMD firestarter jokes, though, so we have to give [GreatScott] credit for that.

Continue reading “How Not To Build A CPU Hand Warmer” →