What can you do with an IR remote? How about anything? Maybe not. We’ll settle for issuing arbitrary commands and controlling tasks on our computer.

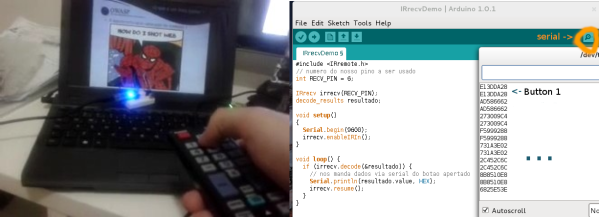

The first step in [Fungus]’s hack is straightforward: buy an IR receiver for a buck, plug it into an Arduino, and load up some IR-decoding code. If you haven’t done this before, you owe it to yourself to take some time now. Old IR remotes are very useful, and dead simple, to integrate into your projects.

But here comes the computer-control part. Rather than interpret the codes on the Arduino, the micro just sends them across the USB serial to a laptop. A relatively straightforward X11 program on the (Linux) computer listens for codes and does essentially anything a user with a mouse and keyboard could — that is to say, anything. Press keys, run programs, open webpages, anything. This is great for use with a laptop or desktop, but it’d also be a natural for an embedded Raspberry Pi setup as well.

Hacking the code to do your particular biddings is a simple exercise in monkey-patching. It’s like a minimal, hacked-together, USB version of LIRC, and we like it.

Thanks [CoolerVoid] for the tip!