These days, paying for TV programming is a fact of life. You pay your cable company or some streaming service and the only question is do you want Apple TV and Hulu or would you rather switch one out for NetFlix? But back in the 1960s, paying for TV seemed unthinkable and was quite controversial. Cable TV systems were rare, and the airwaves were a public resource, so allowing someone to charge to watch TV on the public airwaves was hard to imagine. That was the backdrop behind the Telemeter — an early attempt to monetize TV programming that was more like a pay phone than a modern streaming service.

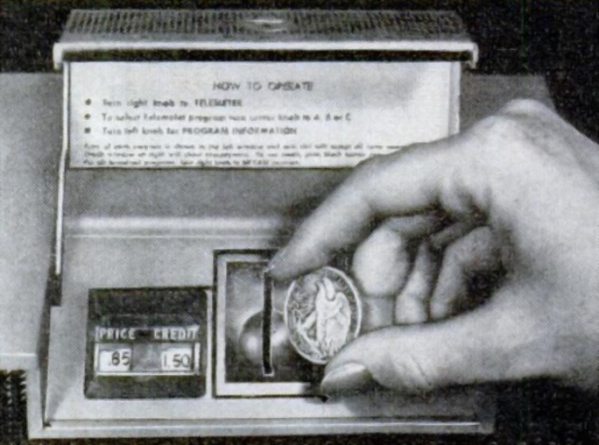

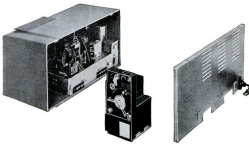

[Lothar Stern] wrote about the device in the November 1959 issue of Popular Mechanics (see page 220). The device looked like a radio that sat on top of your TV. It added a whopping three pay-TV channels, and inside was a coin box, and — no kidding — a tape punch or recorder. These three channels were carried from a Telemeter studio over what appears to be a dedicated cable strung on existing phone poles.

Of course, TVs with coin boxes were nothing new. But those TVs were found in public places, airports, and hotels. The money was simply to turn the TV on for a set amount of time. This was different. A set-top box unscrambled channels delivered over a dedicated cable. Seems like old hat today, but a revolutionary idea in 1959.