It’s a common enough Hollywood trope that we’ve all probably seen it: the general, chest bespangled with medals and ribbons, gazes at a big screen swarming with the phosphor traces of incoming ICBMs, defeatedly picks up the phone and somberly intones, “Get me the president.” We’re left on the edge of our seats as we ponder what it must be like to have to deliver the bad news to the boss, knowing full well that his response will literally light the world on fire.

Scenes like that work because we suspect that real-life versions of it probably played out dozens of times during the Cold War, and likely once or twice since its official conclusion. Such scenes also play into our suspicion that military and political leaders have at their disposal technologies that are vastly superior to what’s available to consumers, chief among them being special communications networks that provide capabilities we could only have dreamed of back then.

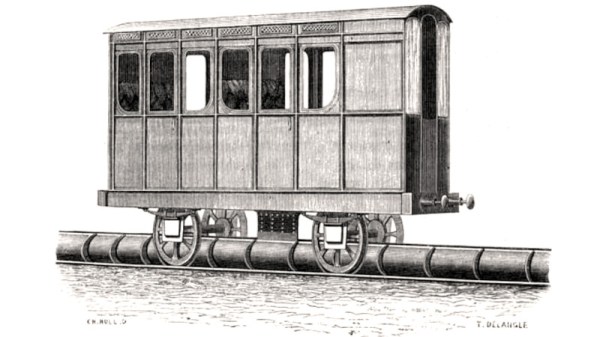

As it turns out, the US military did indeed have different and better telephone capabilities during the Cold War than those enjoyed by their civilian counterparts. But as we shall see, the increased capabilities of the network that came to be known as AUTOVON didn’t come so much from better technology, but more from duplicating the existing public switched-telephone network and using good engineering principles, a lot of concrete, and a dash of paranoia to protect it.

Continue reading “AUTOVON: A Phone System Fit For The Military”