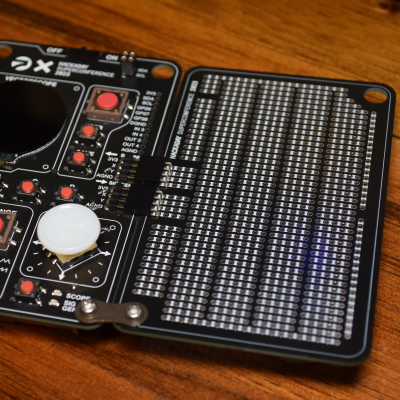

What if you wanted to build your own USB-C PSU? Good news – it’s easy enough! If you ever wanted to retrofit a decent DC PSU of yours to the USB-C standard, say, you got a Lenovo/HP/Dell 19V-20V charger brick and you’ve ever wished it were USB-C, today is the day when we do exactly that. To be fair, we will cheat a bit – but only a tiny bit, we won’t be deviating too much from the specification! And, to begin with, I’ll show you some exceptionally easy ways that you can turn your DC PSU into a USB-C compatible one, with a simple module or a few.

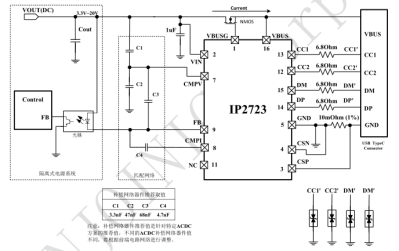

Turning a 20 V PSU into a USB-C PSU feels natural if you want to charge a laptop – those tend to request 20 V from a USB-C PSU anyway, so what’s the big deal? However, you can’t just put 20 V onto a USB-C connector – you have to add a fair bit of extra logic to make your newly christened USB-C PSU safe to use with 5 V devices, and this logic also requires you go through a few extra steps before 20 V appears on VBUS. Any USB-C PSU has to output 5 V first and foremost whenever a device is connected, up until a higher voltage is negotiated digitally, and the PSU may only switch to a higher voltage output when it’s requested to do so.

Turning a 20 V PSU into a USB-C PSU feels natural if you want to charge a laptop – those tend to request 20 V from a USB-C PSU anyway, so what’s the big deal? However, you can’t just put 20 V onto a USB-C connector – you have to add a fair bit of extra logic to make your newly christened USB-C PSU safe to use with 5 V devices, and this logic also requires you go through a few extra steps before 20 V appears on VBUS. Any USB-C PSU has to output 5 V first and foremost whenever a device is connected, up until a higher voltage is negotiated digitally, and the PSU may only switch to a higher voltage output when it’s requested to do so.

Now, for that, a PSU offers a list of profiles, and we looked into those profiles in the Replying PD article – each profile is four bytes that contain information about the profile voltage, maximum current that the device may draw at that voltage, and a few other details. For a PSU to be USB-C compliant, the USB-C specification says that, in addition to 5 V, you may also offer 9 V, 15 V, and 20 V.

Also, the specification says that if a PSU supports certain in-spec voltage like 15 V, it’s also required by the spec to offer all of the spec-defined voltages below the maximum one – for 15 V, that also requires supporting 9 V. Both of these are UX requirements, as opposed to technical requirements – it’s easier for device and PSU manufacturers to work with a small set of pre-defined voltages that majority of the chargers will support, but in reality, you can actually offer any voltage you want in the PSU advertisement; at worst, a device is going to refuse and contend with slowly charging from the 5 V output that you’re required to produce.

I’d like to walk you through how off-the-shelf USB-C PSUs work, all of the options you can use to to create one, and then, let’s build our own USB-C PSU from scratch! Continue reading “USB-C For Hackers: Build Your Own PSU” →