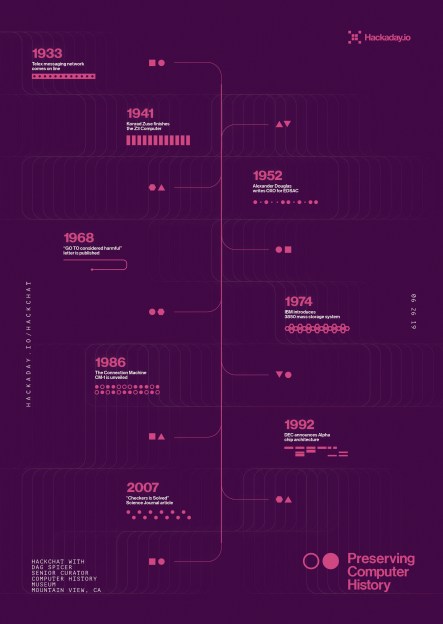

Among the many facets of modern technology, few have evolved faster or more radically than the computer. In less than a century its very nature has changed significantly: today’s smartphones easily outperform desktop computers of the past, machines which themselves were thousands of times more powerful than the room-sized behemoths that ushered in the age of digital computing. The technology has developed so rapidly that an individual who’s now making their living developing iPhone applications could very well have started their career working with stacks of punch cards.

With things moving so quickly, it can be difficult to determine what’s worth holding onto from a historical perspective. Will last year’s Chromebook one day be a museum piece? What about those old Lotus 1-2-3 floppies you’ve got in the garage? Deciding what artifacts are worth preserving in such a fast moving field is just one of the challenges faced by Dag Spicer, the Senior Curator at the Computer History Museum (CHM) in Mountain View, California. Dag stopped by the Hack Chat back in June of 2019 to talk about the role of the CHM and other institutions like it in storing and protecting computing history for future generations.

To answer that most pressing question, what’s worth saving from the landfill, Dag says the CHM often follows what they call the “Ten Year Rule” before making a decision. That is to say, at least a decade should have gone by before a decision can be made about a particular artifact. They reason that’s long enough for hindsight to determine if the piece in question made a lasting impression on the computing world or not. Note that such impression doesn’t always have to be positive; pieces that the CHM deem “Interesting Failures” also find their way into the collection, as well as hardware which became important due to patent litigation.

To answer that most pressing question, what’s worth saving from the landfill, Dag says the CHM often follows what they call the “Ten Year Rule” before making a decision. That is to say, at least a decade should have gone by before a decision can be made about a particular artifact. They reason that’s long enough for hindsight to determine if the piece in question made a lasting impression on the computing world or not. Note that such impression doesn’t always have to be positive; pieces that the CHM deem “Interesting Failures” also find their way into the collection, as well as hardware which became important due to patent litigation.

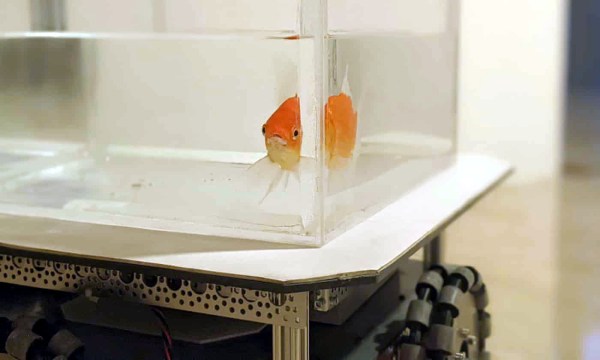

Of course, there are times when this rule is sidestepped. Dag points to the release of the iPod and iPhone as a prime example. It was clear that one way or another Apple’s bold gambit was going to get recorded in the annals of computing history, so these gadgets were fast-tracked into the collection. Looking back on this decision in 2022, it’s clear they made the right call. When asked in the Chat if Dag had any thoughts on contemporary hardware that could have similar impact on the computing world, he pointed to Artificial Intelligence accelerators like Google’s Tensor Processing Unit.

In addition to the hardware itself, the CHM also maintains a collection of ephemera that serves to capture some of the institutional memory of the era. Notebooks from the R&D labs of Fairchild Semiconductor, or handwritten documents from Intel luminary Andrew Grove bring a human touch to a collection of big iron and beige boxes. These primary sources are especially valuable for those looking to research early semiconductor or computer development, a task that several in the Chat said staff from the Computer History Museum had personally assisted them with.

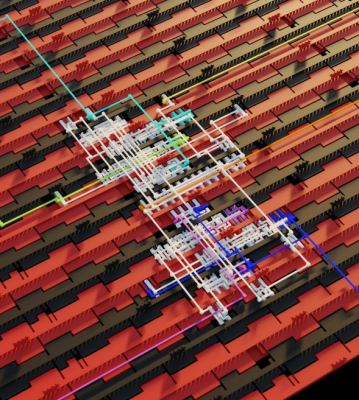

Towards the end of the Chat, a user asks why organizations like the CHM go through the considerable expense of keeping all these relics in climate controlled storage when we have the ability to photograph them in high definition, produce schematics of their internals, and emulate their functionality on far more capable systems. While Dag admits that emulation is probably the way to go if you’re only worried about the software side of things, he believes that images and diagrams simply aren’t enough to capture the true essence of these machines.

Quoting the the words of early Digital Equipment Corporation engineer Gordon Bell, Dag says these computers are “beautiful sculptures” that “reflect the times of their creation” in a way that can’t easily be replicated. They represent not just the technological state-of-the-art but also the cultural milieu in which they were developed, with each and every design decision taking into account a wide array of variables ranging from contemporary aesthetics to material availability.

While 3D scans of a computer’s case and digital facsimiles of its internal components can serve to preserve some element of the engineering that went into these computers, they will never be able to capture the experience of seeing the real thing sitting in front of you. Any school child can tell you what the Mona Lisa looks like, but that doesn’t stop millions of people from waiting in line each year to see it at the Louvre.

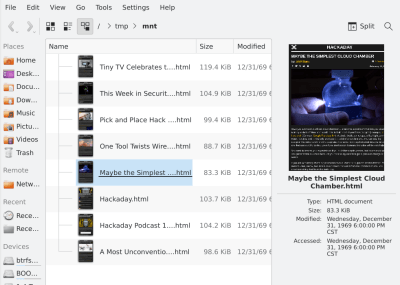

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.