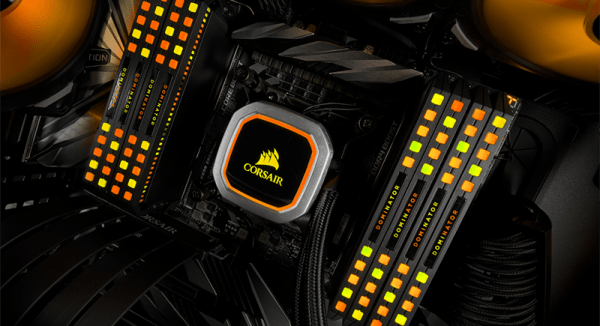

We like blinky things. We’re moths drawn to the flame of serially-addressable RGB LEDs. If the LEDs are smaller, we want to know. If you can drive more of them, we want to know. That said, the most interesting news out of CES last January was both right up our alley, and immensely disappointing. Corsair, makers of RGB computer fans, RGB CPU coolers, and RGB keyboards and mice, have a new product out: RGB RAM, because professional gamers and streamers have a higher win percentage when their RAM is illuminated.

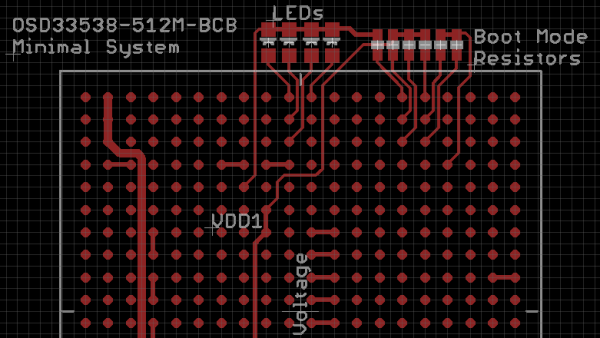

The key innovation of the new Corsair Dominator Platinum RGB DDR4 DRAM is called, ‘Capellix LEDs’. The press surrounding these LEDs gives a clear advantage: right now, the RGB LEDs in your gaming system are mounted in a large SMD package, like a WS2812 or APA101. These large packages reduce LED density, and making LEDs smaller means moar RGB — more colors, or brighter colors, or better efficiency. The key advancement in Capellix LEDs is taking the guts of a serially addressable RGB LED and putting it in a smaller package. Instead of a package that’s 2.8mm³ in volume, the Capellix LED is ‘just 0.2mm³ in size’. The few pictures available of these LEDs give the impression they’re about the size of an 0805 package. It’s small, and we’d like to get our hands on some.

Where these LEDs come from is anyone’s guess, but Corsair did partner with Primax, a Taiwanese manufacturer of computer peripherals, to pull this off. There is no mention of Capellix LEDs in Primax’s press releases, and we don’t actually know if these are the smallest serially addressable RGB LEDs available; we don’t even know if they’re serially addressable. There could easily be a small microcontroller in the Corsair Dominator Platinum RGB DDR4 DRAM, as each stick is only driving twelve individually controllable RGB LEDs.

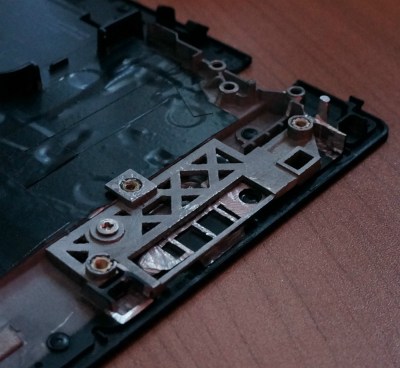

The bottom line is, someone needs to spend $160 for 16GB of RAM, then tear the whole thing apart, preferably with close-up pics of the fancy new RGB LEDs.

A cynical reader would say that Capellix LEDs are simply existing LEDs, the name ‘Capellix’ was trademarked by Corsair, and these LEDs were shoved into a stick of RAM with a significant markup. This, surprisingly, is demonstrably wrong because there is no entry for ‘Capellix’ in the United States Patent and Trademark Office Trademark Electronic Search System. That doesn’t mean the spirit of the cynic is wrong, though; ROHM semiconductors just released a new side-view RGB LED that might be smaller than Corsair’s Capellix LEDs. There are, of course, RGB LEDs available in similar sizes, but none of these are serially-addressable like a WS2812 or APA101. We don’t know what’s in these fancy sticks of RAM, but we’re waiting for someone to do a tear down so we can find out.