Sometimes you’re looking for a component for a project that you know should exist, but you just cannot find it. Something like a 14-segment LED display, but not just one with a fixed color, instead you want some of that sweet addressable RGB-ness. Unfortunately for [EastMakes], this particular display was nowhere to be found, so he decided to try making his own.

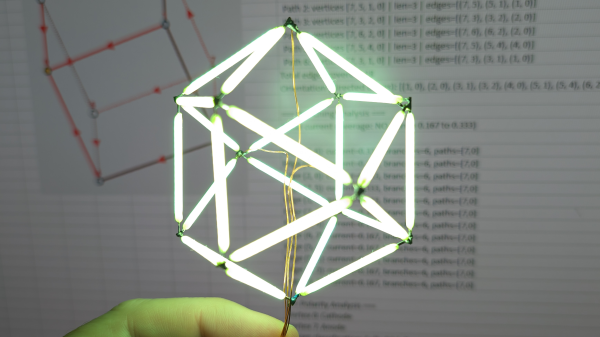

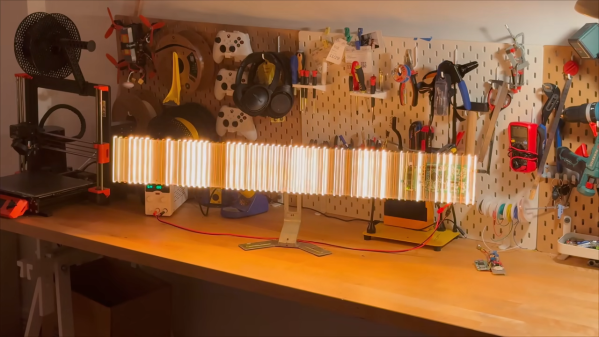

Using addressable SK6805 RGB LEDs with a mere 1.5 x 1.5 footprint as the basis, the layout for these individual LEDs on the PCBs was determined, and a layout created in KiCad. The PCB manufacturing and assembly were straightforward enough — the thing that really makes these displays is the diffuser. Here a few different approaches were tried, including FR4 with translucent segments in the soldermask, and a 3D printed version in both white and black PLA filament.

The FR4 approach using 0.8 mm thin PCBs looked quite all right, with the addition of through vias in the 1 mm version showing how these help to boost overall brightness. The 3D printed version prototypes didn’t look too shabby either, but it would probably help a lot if this diffuser panel also fit around the LEDs to prevent light bleeding between segments.

We’d love to see this type of RGB display being experimented with, as it seems to hold a lot of promise while also definitely being something that ought to exist.

Continue reading “Designing A Compact RGB 14-Segment Display”