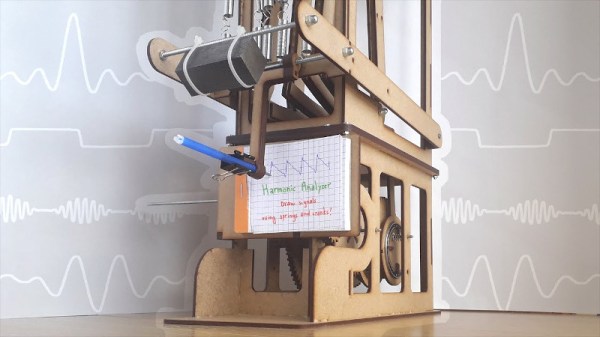

Before graphic calculators and microcomputers, plotting functions were generally achieved by hand. However, there were mechanical graphing tools, too. With the help of a laser cutter, it’s even possible to make your own!

The build in question is nicknamed the Harmonic Analyzer. It can be used to draw functions created by adding sine waves, a la the Fourier series. While a true Fourier series is the sum of an infinite number of sine waves, this mechanical contraption settles on just 5.

This is achieved through the use of a crank driving a series of gears. The x-axis gearing pans the notepad from left to right. The function gearing has a series of gears for each of the 5 sinewaves, which work with levers to set the magnitude of the coefficients for each component of the function. These levers are then hooked up to a spring system, which adds the outputs of each sine wave together. This spring adder then controls the y-axis motion of the pen, which draws the function on paper.

It’s a great example of the capabilities of mechanical computing, even if it’s unlikely to ever run Quake. Other DIY mechanical computers we’ve seen include the Digi-Comp I and a wildly complex Differential Analyzer. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Harmonic Analyzer Does It With Cranks And Gears”