What has 8 ARM cores, 8 GB of RAM, fits in a pocket, and runs NixOS? It’s no pi-clone SBC, but [MWLabs]’s smartphone– a OnePlus 6, to be precise.

The video embedded below, and the git link above, are [MWLabs]’s walk-through for loading the mobile version of Nix onto the cell phone, turning it into a tiny-screened Linux computer. He’s using the same flake on the phone as on his desktop, which means he gets all the same applications set up in the same way– talk about convergence. That’s an advantage to Nix in this application, compared to the usual Alpine-based PostMarketOS.

Of course some of the phone-like features of this pocket-computer are lacking: the SIM is detected, and he can text, but 4G is nonfunctional. The rear camera is also not there yet, but given that Mobile-NixOS builds on the work done by well-established PostMarketOS, and PostMarketOS’ testing version can run the camera, it’s only a matter of time before support comes downstream. Depending what you need a tiny Linux device for, the camera functionality may or may not be of particular interest. If you’re like us, the idea of a mobile device running Nix might just intrigue you,

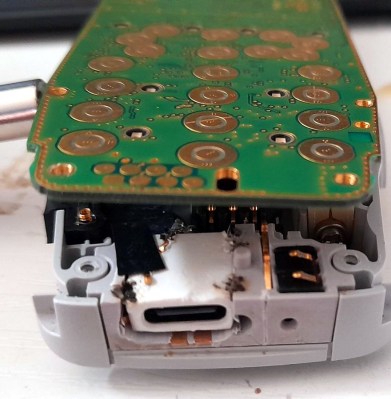

Smartphones can be powerful SBC alternatives, after all. You can even turn them into SBCs. As long as you don’t need a lot of GPIO, like for a server,a phone in hand might be worth two birds in the raspberry bush.