After passing an exam and obtaining a license, an amateur radio operator will typically pick up a VHF ratio and start talking to other hams in their local community. From there a whole array of paths open up, and some will focus on interesting ways of bouncing signals around the atmosphere. There are all kinds of ways of propagating radio waves and bouncing them off of various reflective objects, such as the Moon, various layers of the ionosphere, or even the auroras, but none are quite as fleeting as bouncing a signal off of a meteor that’s just burned up in the atmosphere.

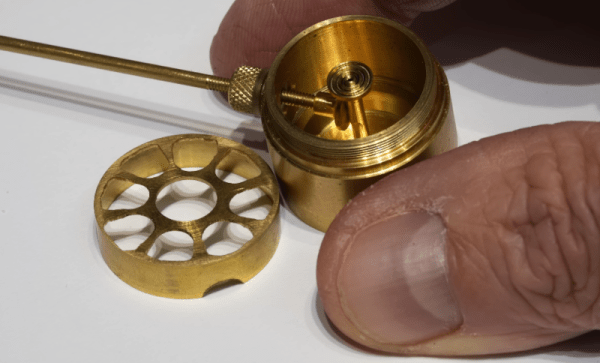

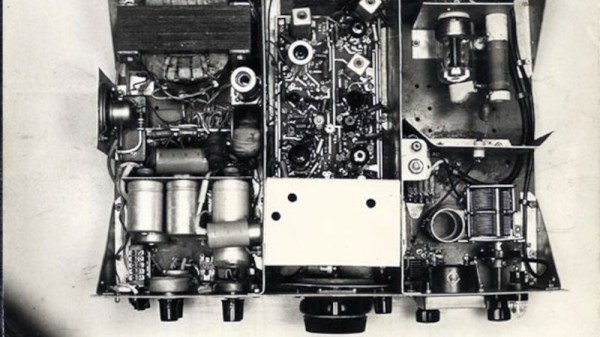

While they aren’t specifically focused on communicating via meteor bounce, The UK Meteor Beacon Project hopes to leverage amateur radio operators and amateur radio astronomers to research more about meteors as they interact with the atmosphere. A large radio beacon, which has already been placed into service, broadcasts a circularly-polarized signal in the six-meter band which is easily reflected back to Earth off of meteors. Specialized receivers can pick up these signals, and are coordinated among a network of other receivers which stream the data they recover over the internet back to a central server.

With this information, the project can determine where the meteor came from, some of the properties of the meteors, and compute their trajectories by listening for the radio echoes the meteors produce. While this is still in the beginning phases and information is relatively scarce, the receivers seem to be able to be built around RTL-SDR modules that we have seen be useful across a wide variety of radio projects for an absolute minimum of cost.