Al Williams wrote up a seemingly innocent piece on a couple of rules-of-thumb to go between metric and US traditional units, and the comment section went wild! Nothing seems to rile up the Hackaday comment section like the choice of what base to use for your unit system. I mean, an idealized version of probably an ancient Egyptian’s foot versus a fraction of the not-quite-right distance from the North Pole to the equator as it passes through Paris? Six of one, half a dozen the other, as far as I’m concerned. Both are arbitrary.

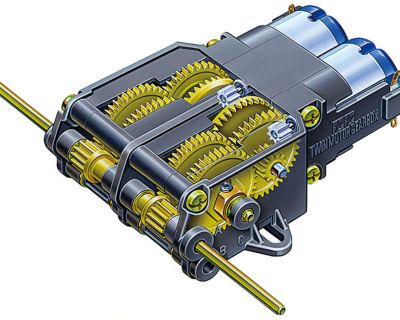

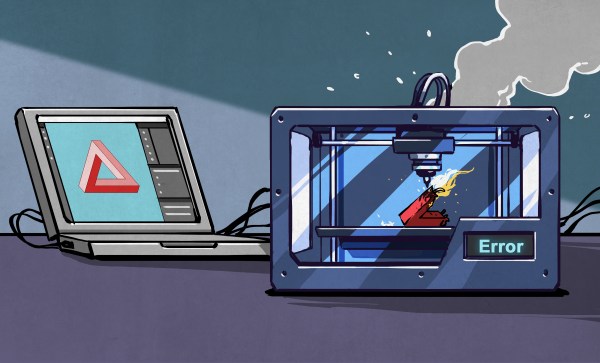

What’s fun, though, is how many of us need to know both systems and how schizophrenic it all can be. My favorite example is PCB layout, where tenths and thousandths of an inch are unavoidable in through-hole and surface-mount parts, yet we call out board sizes and drill bits in millimeters – on the same object, and without batting an eye. American 3D printer enthusiasts will know their M3 hardware, and probably even how much a kilogram weighs, because that’s what you buy spools of filament in. Oddly enough, though I live in Europe, I have 3/4” thread on my garden hose and a 29” monitor on my desk. Americans buy two liter bottles of soda without thinking twice.

The absolute kings of this are in the UK, where the distance between cities is measured in miles, but the dimensions of an apartment in meters. They’ll buy gas in liters and beer in pints. Humans are measured both in feet-and-inches and centimeters, and weighed in pounds, kilograms, or even stone.

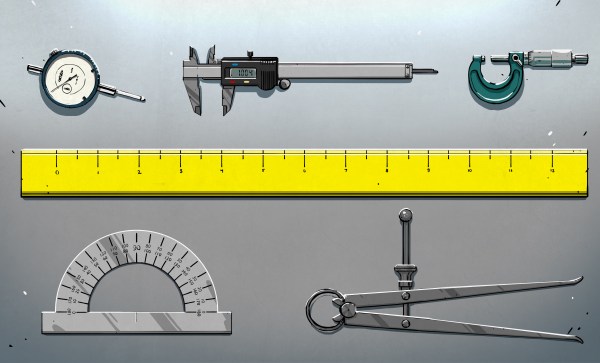

And I think that’s just fine. Once you give up on the rightness of either system, they both have their pros and cons. Millimeters are superb for doing carpentry in – that’s just about how tight my tolerances are with hand tools anyway, and if it’s made of wood, you can fudge 0.5 mm either way pretty easily. Sure, you could measure in 32nds of an inch, but have you ever bought a plywood sheet that’s 1536 x 3072 thirty-seconds? (That’s 4’ x 8’, or 1200 mm x 2400 mm.) No, you haven’t.

But maybe stick to one system when lives or critical systems are on the line. Or at least be very careful to call out your units. While it’s annoying to spec the wrong SMT part size because KiCAD calls some of them out in millimeters and inches – 0402 in inches is tiny, but 0402 in metric is microscopic – it’s another thing entirely to load up half as much fuel as you need for a commercial airline flight because of metric vs imperial tons. There’s a limit to how units-flexible you want to be.