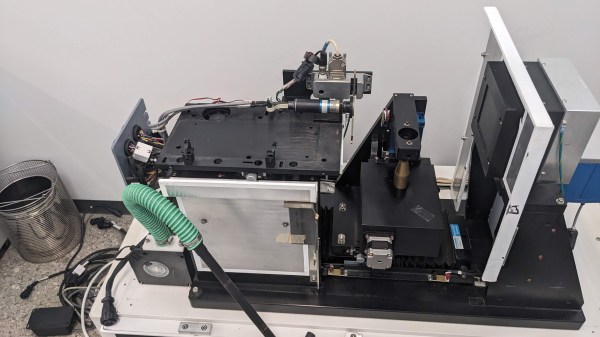

If you have ever wondered what goes into repairing and refurbishing an X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) scanner, then don’t miss [Ahron Wayne]’s comprehensive project page on doing exactly that. He has two small GE Explore Locus SP machines, and it’s a fantastic look into just what goes into these machines.

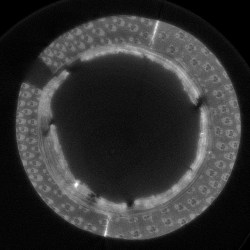

These devices use a combination of X-rays and computer software to reconstruct an internal view of an object. To bring these machines back into service means not only getting the hardware to work correctly, but the software end (including calibration and error correcting) is just as important.

That means a lot of research, testing, and making do. For example, instead of an expensive calibration grid made from an array of tiny tungsten carbide beads, [Ahron] made do with a PCB laden with a grid of copper pads. The fab house might have scratched their heads a little on that one, but it worked just fine for his purposes and price was certainly right.

Tools like these enable all kinds of weird and wonderful projects of their own. So what can one do with such a machine? CT scanning can spot fake AirPods or enable deeper reverse engineering than a regular workshop is normally able to do.

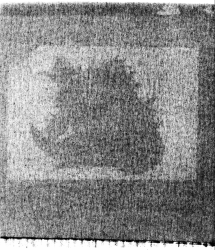

What else? Shown here is an old foil Pokémon card from an unopened package! (Update: the scan is not from a card in a sealed package, it is just a scanned foil card. Thanks to Ahron for clarifying.) [Ahron] coyly denies having a pet project of building a large enough dataset to try to identify cards without opening the packs. (Incidentally, if you just happen to have experience with supervised convolutional neural networks for pix2pix, he asks that you please reach out to him.)

The real power of CT scanning becomes more apparent if you take a look at the videos embedded below the page break. One is a scan of an acorn, [Ahron]’s first successful scan. Another is an interesting scan of a papyrus roll in a bamboo sheath. Both of the videos are embedded below.

Continue reading “X-Ray CT Scanners From EBay, Brought Back To Life”

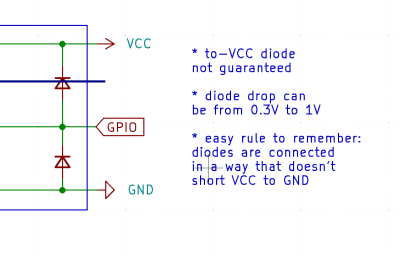

Thankfully, in modern-day Western climates and with modern tech, you are not likely to encounter ESD-caused problems, but they were way more prominent back in the day. For instance, older hackers will have stories of how FETs were more sensitive, and touching the gate pin mindlessly could kill the FET you’re working with. Now, we’ve fixed this problem, in large part because we have added ESD-protective diodes inside the active components most affected.

Thankfully, in modern-day Western climates and with modern tech, you are not likely to encounter ESD-caused problems, but they were way more prominent back in the day. For instance, older hackers will have stories of how FETs were more sensitive, and touching the gate pin mindlessly could kill the FET you’re working with. Now, we’ve fixed this problem, in large part because we have added ESD-protective diodes inside the active components most affected.