You might wonder why you’d repair a calculator when you can pick up a new one for a buck. [Tech Tangents] though has some old Sony calculators that used Nixie tubes, including one from the 1960s. Two of his recent finds of Sony SOBAX calculators need repair, and we think you’ll agree that restoring these historical calculators is well worth the effort. Does your calculator have a carrying handle? We didn’t think so. Check out the video below to see what that looks like.

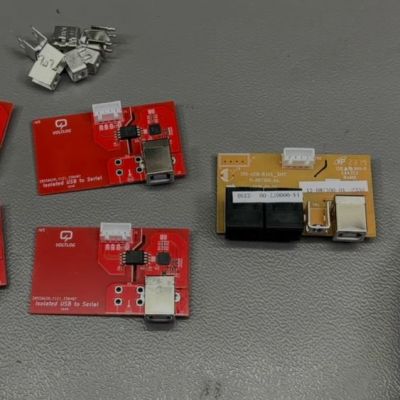

The devices don’t even use modern ICs. Inside, there are modules of discrete parts encapsulated in epoxy. There isn’t even RAM inside, but there is a delay line memory, although it is marked “unrepairable.”

There is some interesting history about this line of calculators, and the video covers that. Apparently, the whole line of early calculators grew out of an engineer’s personal project to use transistors that were scrapped because they didn’t meet the specifications for whatever application that used them.

The handle isn’t just cosmetic. You could get an external battery pack if you really wanted a very heavy — about 14 pounds (6.3 kilograms) — and large portable calculator. We are sure the $1,000 retail price tag didn’t include a battery.

These machines are beautiful, and it is fun to see the construction of these old devices. You might think our favorite calculator is based on Star Trek. As much as we do like that, we still think the HP-41C might be the best calculator ever made, even in emulation.

Continue reading “Repairing Vintage Sony Luggable Calculators”