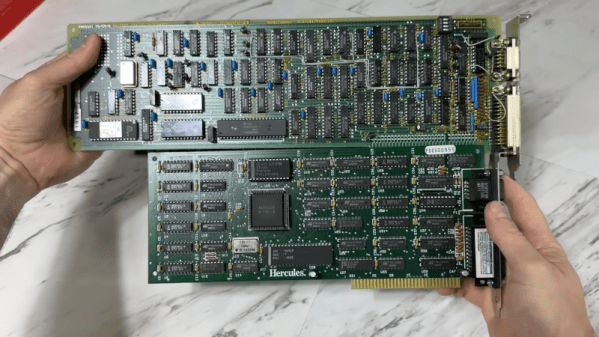

No matter what kind of computer or phone you are reading this on, it probably has a graphics system that would have been a powerful computer on its own back in the 1980s. When the IBM PC came out, you had two choices: the CGA card if you wanted color graphics, or the MDA if you wanted text. Today, you might think: no contest, we want color. But the MDA was cheaper and had significantly higher resolution, which was easier to read. But as free markets do, companies see gaps and they fill them. That’s how we got the Hercules card, which supported high-resolution monochrome text but also provided a graphics mode. [The 8-bit Guy] has a look at these old cards and how they were different from their peers.

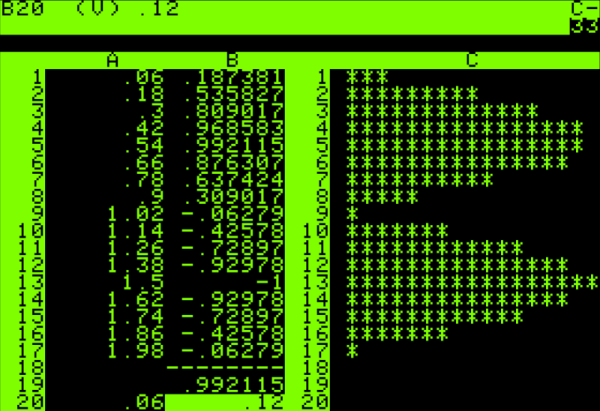

Actually, the original MDA card could do eight colors, but no one knew because there weren’t any monitors it could work with, and it was a secret. The CGA resolution was a whopping 640×200, while the MDA was slightly better at 720×350. If you did the Hercules card, you got the same 720×350 MDA resolution, but also a 720×348 graphics mode. Besides that, you could keep your monitor (don’t forget that, in those days, monitors typically required a specific input and were costly).