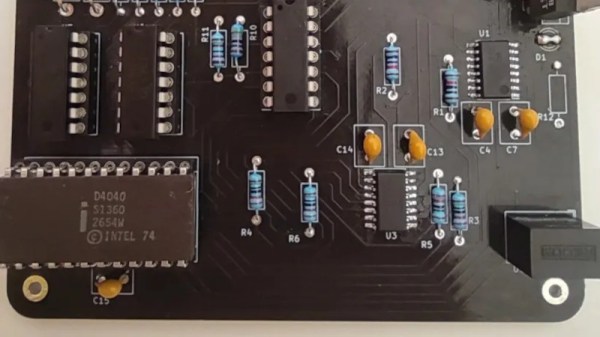

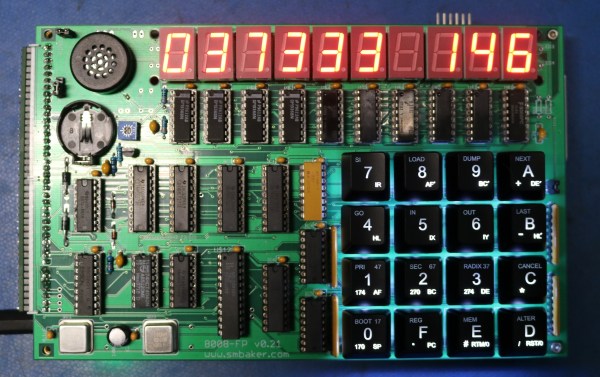

At first glance, getting a computer program to run faster than the first electronic computers might seem trivial. After all, most of us carry enormously powerful processors in our pockets every day as if that’s normal. But [Mark] isn’t trying to beat computers like the ENIAC with a mobile ARM processor or other modern device. He’s now programming with the successor to the original Intel integrated circuit processor, the 4040, but beating the ENIAC is still little more complicated than you might think with a processor from 1974.

For this project, the goal was to best the 70-hour time set by ENIAC for computing the first 2035 digits of pi. There are a number of algorithms for performing this calculation, but using a 4-bit processor and an extremely limited memory of only 1280 bytes makes a number of these methods impossible, especially with the self-imposed time limit. The limited instruction set is a potential bottleneck as well with these early processors. [Mark] decided to use [Fabrice Bellard]’s algorithm given these limitations. He goes into great detail about the mathematics behind this method before coding it in JavaScript. Generating assembly language from a working JavaScript was found to be fairly straightforward.

[Mark] is also doing a lot of work on the 4040 to get this program running as well, including upgrades to the 40xx tool stack, the compiler and linker, and an emulator he’s using to test his program before sending it to physical hardware. The project is remarkably well-documented, including all of the optimizations needed to get these antique processors running fast enough to beat the ENIAC. We won’t spoil the results for you, but as a hint to how it worked out, he started this project using the 4040 since his original attempt using a 4004 wasn’t quite fast enough.