Scoring an interesting bit of old gear on the second-hand market is always a bit of a thrill — right up to the point where you realize the previous owner set some kind of security code on it. Then it becomes a whole big thing to figure out, to the point of blunting the dopamine hit you got from the original purchase.

Fear not, though, because there’s dopamine aplenty if you can copy what [Buy it Fix it] did to decode the PIN on a used generator control panel. The panel appears to be from a marine generator, and while it powered up fine, the menu used to change the generator’s configuration options is locked by a four-digit PIN. The manufacturer will reset it, but that requires sending it back and paying a fee, probably considerable given the industrial nature of the gear.

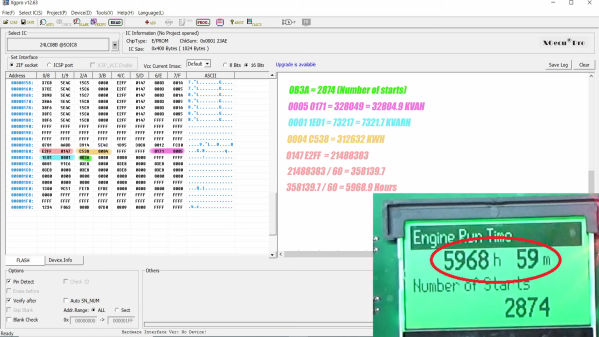

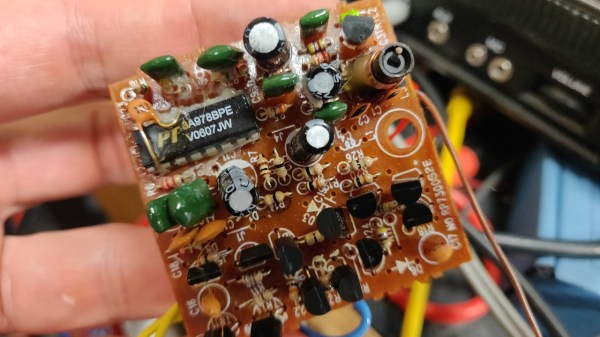

Instead of paying up, [Buy it Fix it] decided to look for a memory chip that might store the PIN. He identified a likely suspect, a 24LC08B 8-Kb serial EEPROM, and popped it off to read its contents. Nothing was immediately obvious, but blanking the chip and reinstalling it cleared the PIN, so he at least knew it was stored on the chip. Many rounds of soldering and desoldering the chip followed, blanking out small sections of memory each time until the PIN was located. The video below edits out a lot of the rework, but gives the overall gist of the hack.

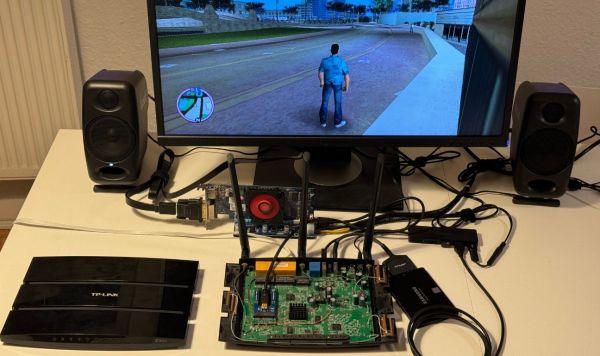

To be honest, we’re not sure if the amount of work [Buy it Fix it] put into this was less than taking a couple of hours to punch in PINs and brute-force it. Then again, if he hadn’t done the reverse engineering he wouldn’t have stumbled upon where the generator parameters like running time and power figures were stored. And it’s not really his style, either; we’ve seen him perform similar heroics on everything from tractors to solar inverters, after all.

Continue reading “Generator Control Panel Unlocked With Reverse Engineering Heroics”